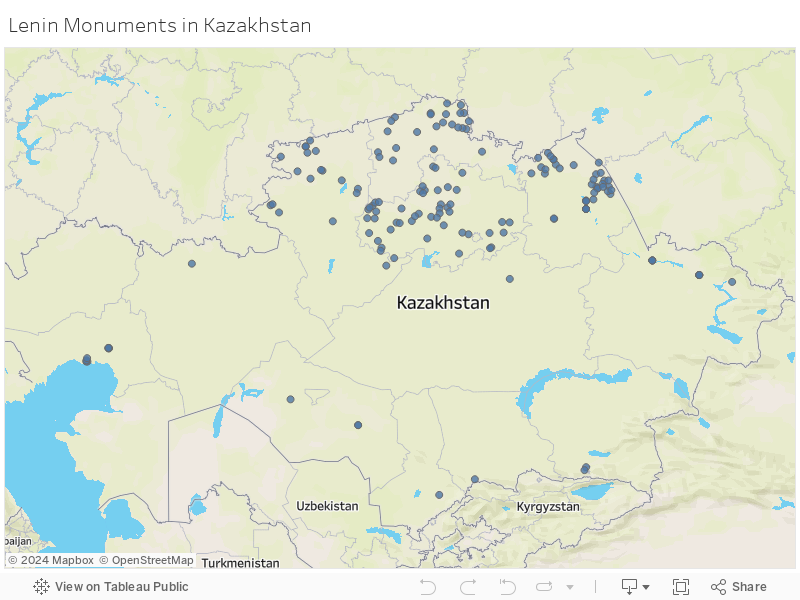

The attempts to grapple with the haunting specter of the Soviet past were by no means unique to Ukraine. Kazakhstan also embarked on its own campaign. Yet the impetus for decommunization has been less robust and the pace rather gradual. With almost 160 monuments remaining (as of 2017), Kazakhstan ranks fourth after Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine in the post-Soviet space in terms of the number of Lenins on its soil. Unsurprisingly, a substantial share of these monuments are in the northern part of the country, near the border with Russia. According to a list published by Tengri News , 84% of the remaining Lenin monuments are concentrated in just four regions: Akmola (49 statues), Pavlodar (43), North Kazakhstan (24), and Kostanay (17), all of which are close to Kazakhstan’s northern neighbor.

Distribution of Lenin monuments in Kazakhstan

It is tempting to discard Kazakhstan’s “reluctant” decommunization as evidence of the pervasive Soviet legacy. But the campaign’s slow pace and limited visibility are a deliberate strategy by Kazakhstan’s authorities, who are striking a delicate balance between domestic nation-building and relations with Russia.

From Core to Periphery

According to the latest available data, 341 Lenin statues have been demolished in Kazakhstan since 1991. Interestingly, apart from dismantling, Kazakhstani authorities have resorted to the strategy of “displacement and replacement.” By relocating Lenin monuments from their central locations to less visible areas, the authorities have deprived these art objects of their unique status while also carving out additional space for new monuments at minimal political cost.

For instance, in Almaty, the Lenin statue was removed from its location in the city center and gave way to the monument dedicated to WWII heroes - Manshuk Mametova and Aliya Moldagulova. The statue of the Soviet leader was relocated to the square in the remote part of the city and eliminated from the list of the state-protected monuments in 2011 – just like the other Lenin monument nearby the “Almaty-1” railway station.

Kazakhstan’s geopolitical position makes any conspicuous “attack” on Lenin monuments politically dangerous. The presence of a sizable ethnic Russian population (just over 18% of the country’s total), coupled with close cultural, political, and economic ties to Russia, heighten the costs of an overt crackdown on the Soviet legacy.

Leninosborniki

Not only have many Lenin statues been relegated to peripheral locations, but they have also been congregated in “Leninosborniki” or collections of Lenins. In Semey, authorities prided themselves on establishing an entire alley of communist statues, including several Lenin monuments, brought from the various quarters of the city to embellish its center. Even more strikingly, the small industrial town of Aksu in Pavlodar region hosts the largest congregation of Lenin monuments in the country. Alongside a host of Soviet-era statuary, Aksu’s central park hosts seven busts and two monuments of the Soviet Union’s founder.

But these “communist sanctuaries” do not necessarily represent a homage to the Soviet past. Lenin parks in many cities are half-abandoned. While Semey’s alley of Lenins may well be an exception, Lenin busts located in Aksu are in relatively shabby condition. Such “communist sanctuaries'' seem a mere formality designed to appease local communists and provide a veneer of respect to the legacy of communism.

Decommunization has long been a contested issue in Kazakhstan. The public remains divided on the Lenin monuments in the country. While some nationalist-leaning groups advocate getting rid of the Soviet legacy altogether, others believe that the Soviet past is an inseparable part of Kazakhstan’s history. On his Facebook page, a Taldykorgani resident Almasbek Sadyrbayev expressed anger over the communist alley in Aksu, referring to the Soviet-era monuments as “statues of devils.” On the other side of the spectrum are residents of Aksu - both the youth and the elderly, who believe that the communist alley should be preserved for its historical significance.

Meanwhile, officials exercise caution in their discourse on the Soviet legacy. Discussions about the Lenin statues in political fora have been rare. But when they do occur, officials are often cautious in denouncing the Soviet past. For example, former communist deputy Vladislav Kosarev labelled the removal of the Lenin monument in the capital a “barbarian act.” In response, then Minister of Culture and Sport Arystanbek Mukhamediuly acknowledged the need to preserve Soviet monuments and even called the public to lay flowers to the Lenin statue in Almaty for the Soviet leader’s birthday.

A gradual decommunization campaign is taking place in Kazakhstan. The government finds itself caught between domestic nation-building goals and foreign-policy imperatives. As a result, the local authorities have adopted a “win-win” strategy by relocating the Soviet-era monuments to the peripheral areas and replacing them with national ones as part of the redefinition of national identity. Such careful maneuvering has been a sound political strategy, which is unlikely to generate significant local grievances around the issue for the time being. Yet, identity politics in Kazakhstan is complex terrain to navigate with contestation between those nostalgists, eager to preserve the legacy of the Soviet empire, and those willing to proclaim: "Goodbye, Lenin!"

Aruzhan Meirkhanova is graduating from Nazarbayev University with B.A. in Political Science and International Relations. The opinions expressed in this article do not represent those of Nazarbayev University.