Against Nike, the Goddess of Slavery: Instagram Artistic Activism Against Forced Uyghur Labor at Nike Sweatshops

An estimated 80,000 Uyghurs from Xinjiang have been compelled to work in factories across China since 2017. This include those who are underpaid and unpaid for their work for at least 82 prominent brands, including Apple, BMW, Nike, Samsung, and Sony. In response, the global community has mobilized in various ways to speak out against the Uyghur rights abuses and boycott the products imported from the XUAR. One interesting avenue of critique has been on social media, where artists have spread their work to draw attention to the issue of forced labor among the Uyghur community. Among these brands, Nike has received the most backlash in social media, where activists have posted amended images of its various products.

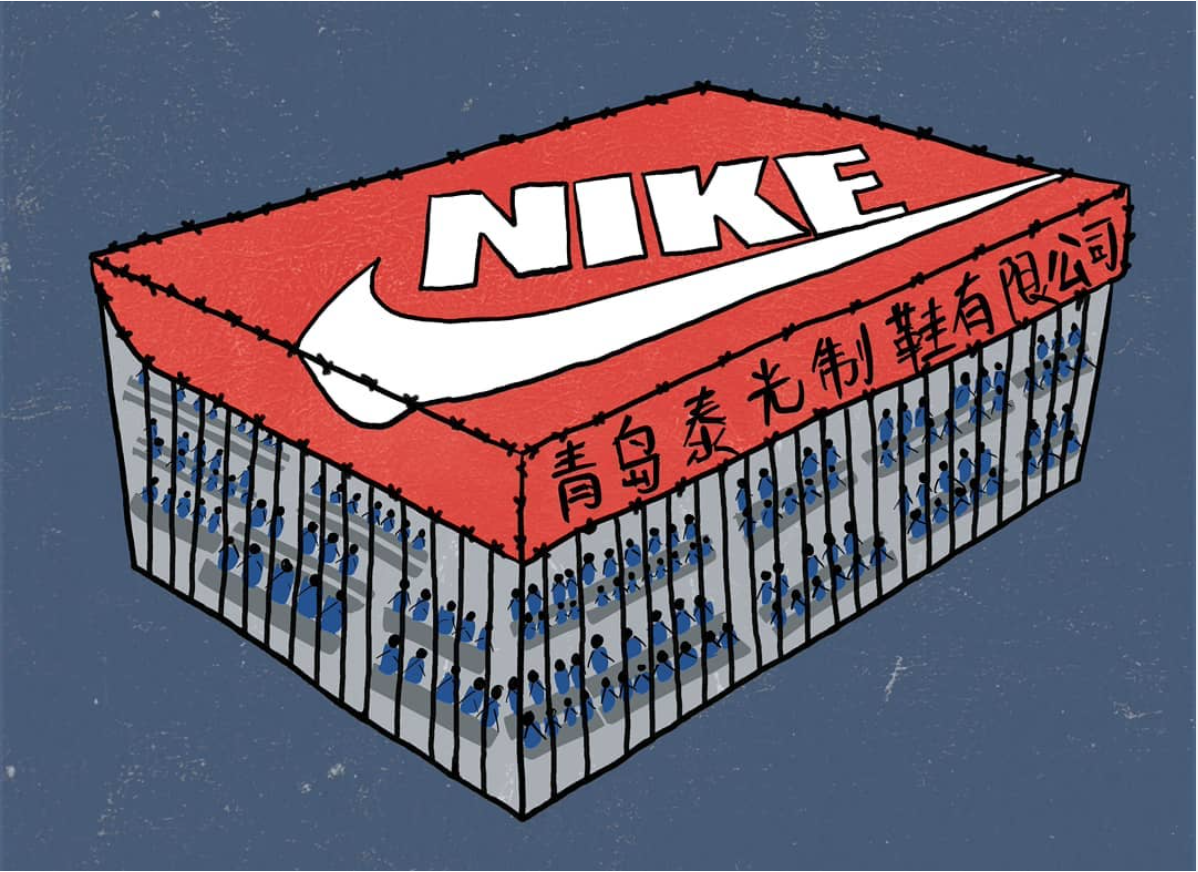

One prominent account @sulu.artco introduces itself as the “artivist collective raising awareness about disappearing Uyghur artists, intellectuals, scholars, entrepreneurs & many more under the Chinese regime” (Sulu.Artco 2021). A post from July 2020 shows a grey shoe box with a red lid and a white “Nike” writing with the Nike Swoosh. The lid is decorated with a thorny prison fence and has Chinese writing on its frontal bend. The lower part of the shoe box has bars, behind which there are around a hundred people turned with their backs in dimmed blue clothes. People seem to sit on benches or at the tables by groups of five.

Digital art posted on @sulu.artco on 17 July 2020

Delving into the deeper meaning of the image, the Nike shoe box connotes a prison, a labor camp, which is inescapable for prisoners because of the thorny fence. The blue clothes resemble the clothes of the Uyghur captives seen in existing photos. The underlying message is one of modern-day slavery, where Nike is a slave-owner operating under Chinese authority.

Some posts turn Nike’s branding on it’s head. For instance, appeals like “Just #dontdoit #nike !” and “Hey #nike, If you think you are a defender of #BlackLivesMatter movement, you should also denounce this crime against humanity !” mock Nike’s prominent slogan. This is written with the aim of undermining Nike’s reputation and calling on the company to adopt positive changes.

Digital art posted on @uyghurstoday on 29 July 2020

Posted by the @uyghurstoday page, the picture shows a Nike sneaker. The image implies that products made by the Uyghur community at Nike sweatshops are made through torture, with the shoelaces dripping with blood. Again, the Nike slogan “Just Do It” is used to denounce and shame the brand.

The following three images were posted by @freeuyghurnow, “a youth-led grassroots movement advocating for the freedom and rights of Uyghurs and Turkic people in internment and forced labor camps.” All of the images are photographs of people wearing Nike clothes modified either by paint or through digital edits. The first one shows a woman posing in a dusty pink color Nike sweatshirt; “FreeUyghur” writing is painted above the Nike logo. The photo is surrounded by dark-red-colored phrases “Call out Nike. Just do it. It can’t wait.” and repeated “free Uyghur” slogans.

Portrait posted on @freeuyghurnow on July 20, 2020

Portrait posted on @freeuyghurnow on 25 July 2020

The above post portrays a man in a Nike jacket with a painted star and the moon, “Free Uyghur” writing and a message in the Uyghur script — all in light blue color, the color of the flag of East Turkestan. In the next image, the Nike Swoosh on the hoodie is crossed out with red color via digital edit. The white text layered on the image states: “FREE UYGHUR. Boycott Nike.”

Portrait posted on @freeuyghurnow on 8 August 2020

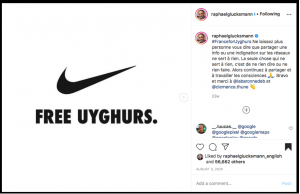

Posted by activist @raphaelglucksmann, this post suggests that Nike should liberate Uyghur workers. In the French-language caption, @raphaelglucksmann uses an English-language hashtag #FranceforUyghurs. It signals the solidarity with the Uyghur community of non-francophones, those outside of France. In other words, the author assumes a transnational character of connective action. He also persuades his Instagram network to “continue to share and work on awareness” / “Alors continuez à partager et à travailler les consciences.”

Digital art posted on @raphaelglucksmann on 3 August 2020

Although some might argue that posting on social media is slacktivism, in the context of the ongoing global pandemic, digital activism makes mobilizing for social causes possible even with the borders shut down and mass gatherings prohibited. These artworks have generated a great deal of attention on social media, resulting in a burst of thousands of comments addressing the fate of Uyghurs under Nike’s posts on Instagram. This is clearly working. Despite ignoring such messages on Instagram, Nike did release a statement on Xinjiang, admitting that it “conducts ongoing diligence with our suppliers in China to identify and assess potential forced labor risks related to employment of Uyghurs.” In response to the statement, which also committed Nike to not use cotton from Xinjiang, users of Chinese social media platform Weibo called for a boycott of Nike products. Some went as far as publicly burning Nike-branded products. This indicates that social media activism is having an impact.

Tomiris Mashan is a recent graduate of Nazarbayev University. She presented a version of this paper at the European and Eurasian Undergraduate Research Symposium by the University of Pittsburgh.