Revolution and Rising Discontent: An Update on the Central Asia Protest Tracker

This report is based on the Central Asia Protest Tracker. Download our full dataset.

By Natalie Simpson, Raushan Zhandayeva, Sher Khashimov and Samuel Elzinga

Barely twenty-four hours after the polls closed in Kyrgyzstan’s flawed parliamentary election in October, protesters stormed and occupied the White House, the home of Kyrgyzstan’s executive and legislative branches. The people of Kyrgyzstan woke up the next morning to images of protesters drinking tea in President Soronbai Jeenbekov’s office while politicians who had just been sprung from prison held rallies on Ala-Too Square. Overnight, the protesters had managed to fracture Kyrgyzstan’s political status quo. The next few days would see over a hundred protests all across the country, as competing politicians, groups, and interests took to the streets with the goal of influencing Kyrgyzstan’s future, seizing government buildings to appoint their representatives and seizing assets owned by foreign investors.

From September to December 2020, protests played a central role in shaping Kyrgyz politics. While less influential across the rest of the region, protests have nevertheless served as a crucial outlet for political, economic, and social dissent. Over this period, the Central Asia Protest Tracker (CAPT) dataset produced by the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs recorded a total of 596 protests across the region. Of these, 254 occurred in Kazakhstan, 250 in Kyrgyzstan, 72 in Uzbekistan, eight in Turkmenistan, and just two in Tajikistan. The CAPT database consists of online published material that is public and identifiable, but not private. More information on our methodology and coding can be found in our codebook.

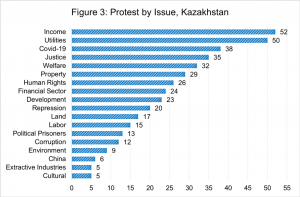

Issues relating to income, property, and welfare have been the prime motivators behind dissent, with Covid-19 serving to accelerate these trends with business closures and growing wage arrears in all economic sectors. This connection between Covid-19 and economic issues was especially visible in Kazakhstan, where 15 percent of all protests were connected to the pandemic. Utilities were another major driver of protest activity in Central Asia, with 72 protests, 68 of which took place in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, where people were left without heat as winter temperatures set in. In Uzbekistan, one-third of protests were linked to issues of redevelopment and property, as activists continue fighting attempts to demolish homes and evict residents as the country goes through a government-backed modernization process. Protests in Turkmenistan largely revolved around economic issues such as food security, income, and welfare, in keeping with the broader trends in the region and the restrictions on political expression in the country. Justice — in particular, demands for the release of political prisoners — was another major issue driving protests in Kyrgyzstan. This trend was also true in Kazakhstan; roughly 14 percent of protests in each country were connected to the operations of the judicial system. In Kazakhstan, however, more of these protests were connected to repression and human rights, and a cluster of protests emerged surrounding the deaths of political activist Dulat Aghadil and his son

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan experienced a sharp uptick in protest activity as a result of the October parliamentary elections and subsequent political turmoil. According to CAPT, 250 protests occurred in Kyrgyzstan between September 1 and December 31. Protests sparked by widespread discontent over vote-buying in the October parliamentary election led to the resignation of President Jeenbekov and the ascendance of Sadyr Japarov. On October 5, the day after the election, the biggest protest swept Bishkek’s Ala Too Square, where 8000 people gathered to condemn the falsified election results. Within just one week of the October 4 parliamentary elections, 110 protests took place across the country. After months of intense protest activity, there was even a “protest against protests” in December.

After Japarov became the acting president in mid-October, a new wave of peaceful, election-related protests in opposition to Japarov and his proposed constitutional changes began. These protests against the “Khanstitution”, a term mocking what is perceived to be a consolidation of power, attracted mainly young, urban liberals, but did not reach beyond Bishkek. They also remained much smaller and less widespread than the post-election protests a few weeks earlier, and the movement ultimately did not achieve its goal of halting the referendum on Kyrgyzstan’s form of government. The most prominent group involved with these protests was the Bashtan Bashta movement, which organized weekly marches in Bishkek throughout the fall and winter. Much like Kazakhstan’s Oyan Qazaqstan movement, Bashtan Bashta is a youth-led, pro-democracy movement that has avoided traditional party-based political engagement in favor of civil society activism.

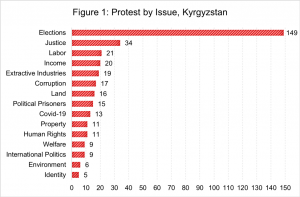

The issue of elections dominated the protest landscape in Kyrgyzstan, accounting for 60 percent of protests (149 events). This four-month period represents nearly three-quarters of all human rights-related protests in Kyrgyzstan across the entire CAPT dataset, reaching back to January 2018. The majority of these protests were connected to rigged election outcomes, calls for the release of political prisoners, the proposed amendments to the constitution, and the decision to hold a constitutional referendum. Protests against the country’s justice system accounted for 14 percent of all protests. Prior to, and in the immediate aftermath of, parliamentary elections, the majority of demands were related to the release of political prisoners and complications with the registration of political parties. In several cases, protesters took the initiative to release political prisoners by breaking into law enforcement facilities. On October 6, while protesters in Bishkek released prisoners who were arrested in relation to the Koi Tash events in 2019, not far from the capital, protesters freed the former Prime Minister Sapar Isakov. On the same day, after a riot and subsequent surrender of special forces, former President Almazbek Atambayev was released from a pre-trial detention center. In the given period, a dozen protests targeting the justice system concerned fair trials and the release of Almazbek Atambayev.

The power vacuum created by the parliamentary elections led to a spike in protests related to the mining industry, which accounts for around 10 percent of GDP and has been the source of ongoing contention with the local population. Between September and December 2020, protests targeting extractive industries accounted for 8 percent of all protests. In the immediate aftermath of the contested October election, companies in the field of extractive industries came under heavy attack from protesters. On October 6, there were 10 protests related to extractive industries; three additional attempted asset seizures took place on October 7. Protestors seized companies’ offices, looted buildings, and destroyed property. For instance, the Kyrgyzaltyn gold refinery in Kara Balta was seized, and the company’s office in Bishkek was targeted three days in a row by people trying to take over the firm. Some of the attempted asset seizures also reflected growing anti-China sentiment, as several Chinese-owned mines were attacked by local residents and Chinese employees were expelled from a mine in Ishtamberdi.

While more than half of the protests in Kyrgyzstan were related to the elections, other issues that caused large numbers of protests included labor (21 cases), income (20 cases,), corruption (17 cases), and land (16 protests). Like in Kazakhstan, income-related protests were due to delayed payments and the closure of enterprises stemming from the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, workers in the service and mining sectors demanded the opening of markets and mining enterprises. On September 29, around 100 restaurant and cafe workers voiced their concern about 5,000 people who lost their income as a result of closures.

The post-election chaos in the extractive industries sector also ended up sparking protests later in the year, as many mines were forced to shut down. In December, around 200 workers from the Bozymchak mining company protested in Bishkek, demanding that the mine restart work. Work at the mine had remained suspended since October 7, and the workers said that they needed operations to resume in order to earn wages and provide for their families. The majority of labor-related protests demanded the resignation of company heads and directors of organizations who were deemed either corrupt or unresponsive to employees’ hardships.

As the above examples indicate, in addition to rallies and marches, common tactics used by protesters contesting the election outcome included attempted asset seizures at resource companies and other buildings (17 cases) and confrontations (16 cases). Overall, peaceful protest tactics prevailed, with only slightly over 10 percent of all protests being violent or disruptive.

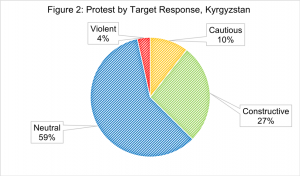

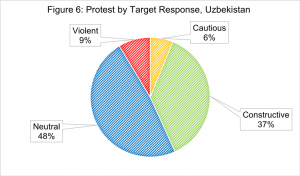

Kyrgyzstan’s political system remained relatively tolerant of protests — the government responded with violence in only 4 percent of incidents — but Kyrgyzstan also had the lowest rate of constructive response to protest in the region. In Kyrgyzstan, only 27 percent of protests had a constructive response, as compared to 46 percent in Kazakhstan and 37 percent in Uzbekistan. Within Kyrgyzstan, the rate of constructive response dropped to 27 percent from 36 percent (the rate from January 2018 through August 2020). These statistics likely reflect the sheer volume of protests taking place during the chaotic recent months, as well as the relative prevalence of political protests with sweeping demands in Kyrgyzstan, as compared to other, less open Central Asian countries. But the internal shift in receptiveness to protests also suggests that protest is becoming a less effective tool of political action in Kyrgyzstan, as the country grapples with widespread political fatigue and the acceptance of an increasingly authoritarian regime.

Our regression analysis on the CAPT dataset examined several factors associated with the government response to protests in Kyrgyzstan. Holding a protest in Bishkek is associated with a nearly 300 percent increase in the probability of a violent response and a 83 percent decrease in the probability of a constructive response. A connection to opposition groups and using violent protest tactics are both associated with a decrease in the probability of a constructive response — by 63 percent and 72 percent, respectively — though they do not have a statistically significant association with the probability of a violent response.

Kazakhstan

Protest activity in Kazakhstan between September and December of 2020 shows a regime fighting to maintain its legitimacy amid the Covid-19 pandemic, with 80 percent of 254 protests targeting the local and national governments. Covid-19 became the largest economic shock the country’s economy has experienced in the last two decades. The conjoined effect of economic and health crises limits the ability of the government to respond to either effectively, ultimately undermining its political capital. In July 2020, the World Bank projected that the country’s GDP would contract by 3 percent in 2020 and further exacerbate inequality: the poverty level may increase from 8.3 percent to 12.7 percent forcing 800,000 more people into poverty.

The pandemic and its impact on the country’s economy thus have dominated the political landscape in Kazakhstan over the reporting period. While CAPT registered only 38 protests directly related to restrictions aimed at stopping the spread of Covid-19, the pandemic’s effect is evident from other protest activities. Over 80 protests – the highest number among Central Asian countries – were related to government service provisions like welfare, Covid-19 relief, and provision of utilities. On October 6, 2020, over a hundred residents of Saryagash protested against poor infrastructure and the absence of natural gas supply; just a month later, over a hundred residents of Ust-Kamenogorsk demanded that local authorities fix collapsing infrastructure in town. There is also an on-going trend of mothers with many children protesting the lack of social welfare support and demanding the local and national governments to provide it. On November 23, 2020, about 50 women gathered outside of Shymkent’s city administration demanding a meeting with a city mayor over issues pertaining to households with multiple dependents, including the quality of government-subsidized housing. These protests constituted a third of all activity in Kazakhstan and demonstrate the deteriorating economic conditions in the country.

The effect of the pandemic on the economic conditions is also evident in the protests surrounding the issues of livelihood that constituted over a quarter of all protest activity in Kazakhstan. On December 2, 2020, over 300 workers of the Aktyubinsk Petroleum Machinery Plant protested against the planned relocation of their facility; just over a week later, 300 workers of a railroad service company protested in Zhezkazgan demanding pay raise. Another notable trend is the small-scale protest activities of essential workers. There were multiple rallies organized by healthcare workers that demanded additional financial support during the pandemic. For example, on December 24 2020, 30 medical workers in Almaty gathered to protest the absence of the pandemic allowances promised by President Tokayev.

The reported period was also marked by over a 100 protests related to the country’s democracy and civil rights issues, highlighted by the buildup for the January 2021 parliamentary elections. On September 13, 2020, over 200 people gathered in Almaty to protest the law about peaceful demonstrations. On December 16, 2020, a large group of protesters associated with the Oyan Qazaqstan movement and the Democratic Party of Kazakhstan were surrounded by police and kept in cold weather for over three hours as they demanded parliamentary reforms.

Regression analysis indicated that connections to opposition groups is associated with a 900 percent increase in the probability of a violent response from the government and a 92 percent decrease in the probability of a constructive response. Both of the numbers are indicative of limited space for opposition activities in the country. Additionally, holding a protest in Nur-Sultan is associated with a 171 percent increase in the probability of a violent response; using violent protest tactics is associated with a 413 percent increase in the probability of a violent response from the government. Interestingly, holding a protest against the government, local or national, is associated both with a 81 percent increase in the probability of a violent response and a 77 percent increase in the probability of a constructive response from the government. This might suggest that the nature of the response is predicated on central issues of protests rather than on the degree of anti-government sentiment.

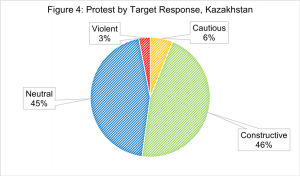

During the reported period, about two-fifths of all protests took place in the country’s three largest cities, Almaty (45), Nur-Sultan (29), and Shymkent (26). Despite the growing antagonism between the economically strained population and the government, the Kazakh regime showed the most restraint in its response among the five Central Asian governments over the reported period, with only three percent of protests invoking a violent response from the government in the form of arrests, intimidation, or penalties. This is in stark contrast to the period between January 2018 and August 2020, when over a quarter of all protests ended in arrests or use of force. Over 90 percent of the government’s response – the highest share among the Central Asian countries – was constructive or neutral.

Uzbekistan

Following Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan counts a total of 72 protests from September to December 2020. Around 43 percent of the protests took place in the capital, Tashkent, with the remainder being spread out among 28 other regions in Uzbekistan and Andijon having the highest protest occurrence rate (7 percent) after the capital. According to the World Bank Listening to Citizens of Uzbekistan study, the economic situation in Uzbekistan has taken a major toll since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the unemployment rate has risen to 10 percent and, therefore, around 450,000 more people are expected to fall below the poverty line. Likely as a result of these trends, protests in Uzbekistan nearly doubled in 2020 when compared to combined 2018 and 2019 data. However, only 3 protests in that period were directly related to the Covid-19 pandemic.

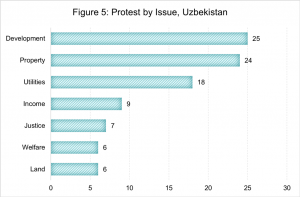

According to the CAPT methodology, the top three most recurring themes for protests in Uzbekistan are development (34 percent), property (33 percent) and utilities (25 percent).

A lack of a legal definition of land ownership, chaotic and inconsistent building construction across the country and the permissiveness of the authorities in decision-making have led to violations of rights and the interests of homeowners. Residents of Tashkent tend to protest against construction of new residential apartment buildings or commercial buildings due to limited spacing and safety and environmental concerns. According to CAPT data, protests as such are usually met with no further action/acknowledgment from construction companies or local authorities, despite the existence of two protests in which promises were made, in September, residents of Nurobod demanded the return of the football field for public use, and in the same month Tashkent residents claimed illegal raiding and demolishing of private storage rooms.

More than half of the protests in the month of December were caused by the energy crisis in Uzbekistan. Unusually severe low winter temperatures in Uzbekistan showcased the inability of the government to provide basic necessities such as electricity, gas and heating. On December 27, Muzrabat locals, in which 165 families were left without electricity, protested by blocking roads and setting tires on fire. Similar protests also occurred in Andijond, Kokand, Karakul. The government blamed minor technical issues for the plants as well as the lack of investment in the energy sector in the past 30 years.

The largest protest of 2020 took place in October 2020, where around 1,000 protesters stormed the Uzbekistan GLT factory in Guzar after the 4-month delay in payment and lack of access to food. The protest was quickly de-escalated with detentions by the Uzbekistan National Guard and State Security forces. Half of the protests targeted local and national government and 45 percent targeted local non-governmental actors such as businesses and individuals. Neutral and constructive responses make up 85 percent, of which 7 cases (8.5 percent) have been violent. As an example, around 35 Nukus protestors gathering to express frustration against government repression against political activists have been detained and penalized. Protests in Uzbekistan are still of rare occurrence, however, compared to Kyrgyzstan. Most of the gathered data show protest patterns on a smaller scale, such as dissatisfaction with local government and businesses

Turkmenistan

Food shortages in state-subsidized stores and paucity of cash across the country continue to be main reasons behind ongoing protests in Turkmenistan. In the period between September and December 2020, out of overall eight protests, two were related to lack of food supplies and another two to the inaccessibility of cash in banks. Shortage of food supplies in state stores such as flour, eggs, and cooking oil has been common since the economic crisis in 2016 brought on by falling gas prices and a fall in the value of the national currency. But in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused the situation to become even more acute.

Last November, residents of Garagum district protested in front of the local government office demanding the provision of delayed flour ratios that constitute 1 kg of flour per person for 1 month. In December 2020, the same problem was brought up when about 50 women protested in front of the local government office in Mary, expressing grievances in regards to supply of flour and lack of drinking water in rural areas.

Cash shortages also prevent Turkmenistan’s citizens from accessing food and other staple goods. In the given period, Turkmenistan’s citizens protested twice in relation to the unavailability of cash. On 25 September 2020 around 300 residents of Balkanabat gathered in front of the regional prosecutor’s office after another failed attempt to withdraw cash from a bank. While the protest in Balkanabat had a successful outcome and protesters were able to access cash, it is a unitary case against the backdrop of the pervasive problem of cash shortage since 2019. Already by July 2019, Turkmenistan’s citizens were experiencing delays in pensions and other state benefits. Although the government respondent constructively in seven out of the eight cases, overall the authorities have not taken actions to address the underlying causes of the protests.

Conclusion

While the turbulence of the last few months in Central Asia has died down with elections in both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in January, the struggles faced by many people in Central Asia remain. The new executive in Kyrgyzstan and the new legislature in Kazakhstan still face the economic challenges of the pandemic, scrutiny from international observers regarding their treatment of protesters, and shortages of necessities. Meanwhile, continued protest activity sparked by development projects in Uzbekistan signals that the tensions surrounding the state’s modernization push are unlikely to dissipate. Likewise, in Turkmenistan, the government’s inattention to the root economic causes of discontent suggests that similar protests may recur in the future.

While state responses to protests across the region remain largely neutral or constructive, there are indications that this trend may not hold. Police in Kazakhstan just days ago kettled a small group of peaceful protesters in Almaty. Incidents of kettling are becoming increasingly common after the January 10 elections in Kazakhstan, which potentially signals the adoption of new tactics by Kazakhstani police. The transition to a purely presidential system in Kyrgyzstan may also impact the ability of protesters to gather peacefully, or itself draw protests should the new regime fail to live up to its promises. As such, it remains vital to continue monitoring protests in Central Asia.