The Silk Road: A Living History

In 2019, photographer Christopher Wilton-Steer traveled overland from the United Kingdom to Beijing to document the historic Silk Road as it looks today. His journey took four months, covered 40,000 kilometers and sixteen countries, and yielded some 50,000 photos, a selection of which is now on exhibit in Granary Square, London, from 8 April 2021 through 16 June 2021. The Oxus Society sat down with Christopher to learn more about his journey and work.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about the trip—where did you go, and why did you select that route?

This trip is where my personal and professional interests came together. My first job out of university was in Beijing working for a publishing company, and that was obviously a world away. I remember flying over, on the way, and just looking out the window and thinking, what’s in between all of this? When I was in Beijing, some people I’d heard of had motorcycled back to France. And I just thought, wow, what a journey that is. I always loved traveling and had enjoyed it from a young age. So, I just thought, this is the ultimate journey. And of course, that was in 2007. So, that’s quite a long time ago, and I always wanted to do one great trip in my life—hopefully more than one, but I want to do one great trip. I always had this in the back of my mind.

When I was working with the Aga Khan Foundation, which I started in 2013, I started traveling a lot more to Central Asia and the South Asia region just for work and started to fit together this puzzle of how a trip like this could work. As a photographer, I was advancing in a sense and wanting to do more with it. I had this idea: wouldn’t it be great to have an exhibition of photographs that allowed you to travel—the visitor, that is—through and take this journey themselves and see how these cultures reference each other, the connections between them. It’s not just a travel exhibition, or photography exhibition, but one that you can take your own journey through as well.

Working with the Foundation, we do a lot of work in that part of the world and have done for decades, whether it’s traditional development work around education, food security, early childhood development, health and nutrition, things like that, to the restoration of historic buildings such as Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi or forts in northern Pakistan. We have a music initiative supporting Central Asian musicians to transmit their knowledge and to promote them in parts of the world that otherwise might be difficult to access. We have this important story to tell about the work we do in Central Asia. So, I just thought this would be a way to tell it through the framing of the Silk Road. It was a way to tell a story, both about the cultures that lay along it and a story about our work, engaging with some of those cultures. So that that was the essence of it.

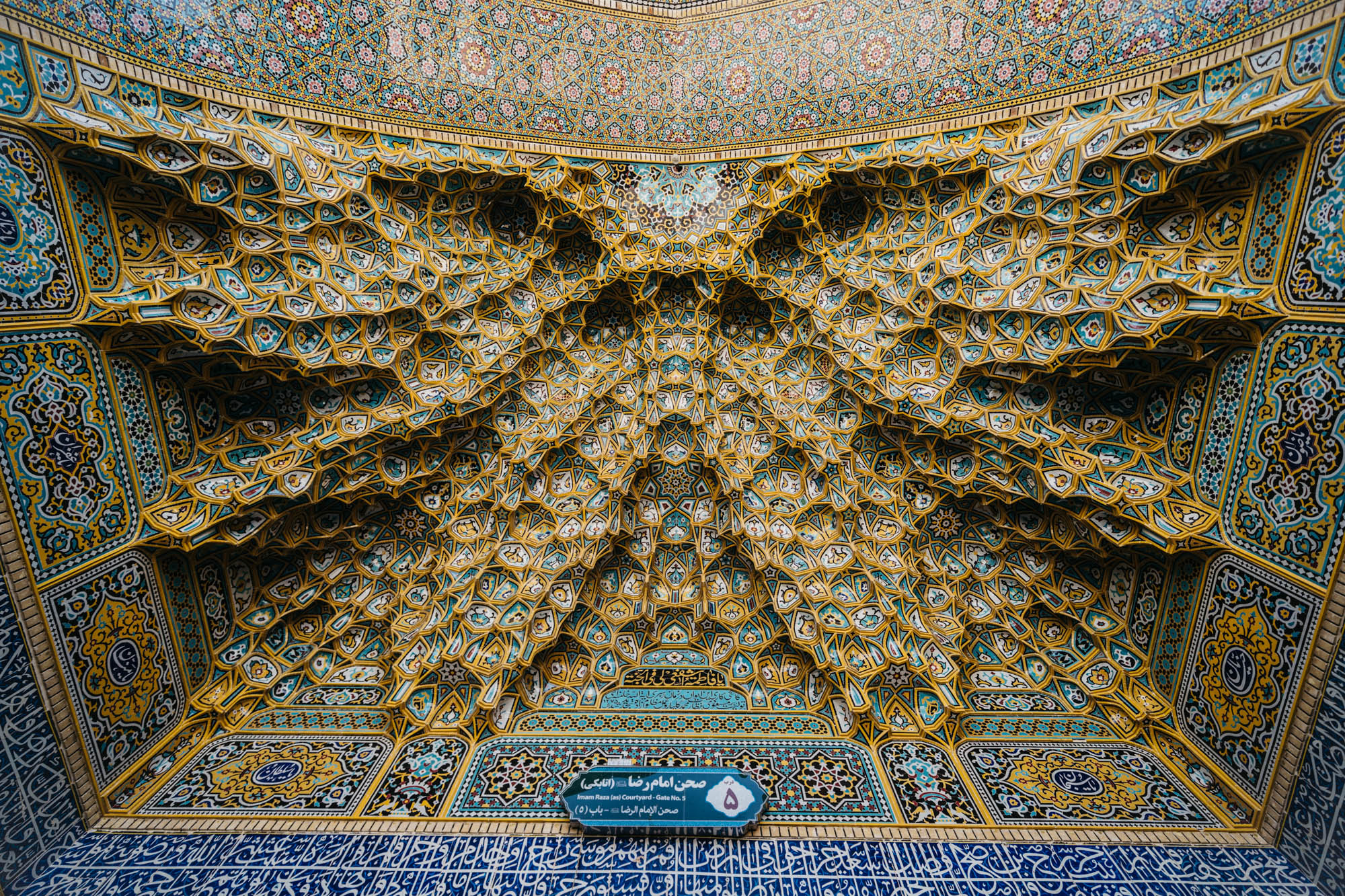

Why that route? Well, I wanted to start from London. For a London-based exhibition (although I hope it will travel), I thought it’d be nice for people from the UK, rather than starting in Pakistan or Turkey or somewhere that was already quite far away and foreign, the idea is that you could launch from your own country and start this journey. The route I picked was direct-ish. I wanted to get across Turkey because Istanbul was so important to the Silk Road. Then Iran. I had never been to Iran before, so this was a great opportunity to go and do that. The rest of it is more or less in a straight line. I would have crossed Afghanistan, but I couldn’t, and so had to take a several 1000-kilometer detour to Pakistan. I took a flight to Dubai, then Islamabad, and then traveled up to the north again. So, there were, unfortunately, some flights, but they couldn’t be helped. You can see parts of the old Silk Road, the path that the traders took, in northern Pakistan, so I had to go and capture some of that as well. Then, China is obviously the terminus of the Silk Road, so that that was the obvious choice to end. I went through the Khunjerab Pass between Pakistan and China into Xinjiang and then went across the Taklimakan desert, or north of it, to Ürümqi, then across to Turpan and Xi’an, and then eventually Beijing.

When you say that you can see evidence of the Silk Road in places like northern Pakistan, what do you mean by that?

In northern Pakistan, roads follow the river systems and the valleys because that’s the obvious safest place to travel, rather than at the top. So, you’ve got the Karakoram Highway, which is the main thoroughfare that connects China with Pakistan. On the other side of the river at points, there’s a little trail that snakes across the side of the mountain. That was the original road, which is where the traders would bring stuff from Xinjiang across to Pakistan and beyond, into Central Asia. And so, that heritage is still alive, and the Aga Khan Foundation has restored some of that road to make sure that some of this old Silk Road still exists.

When I was in Kashgar, to cross the border, you must take a minibus up to the Chinese border. The border crossing took about six hours, and I sat in the front of the bus with this old man. I had some dried fruit, so I was sharing it with him. He didn’t speak English, and I didn’t speak Urdu. So that was the extent of our exchange, and then we parted ways in Tashkurgan.

A few days later, I saw him in Kashgar, and he was in a shop selling antiques out of his suitcase to a Uyghur shopkeeper. They weren’t even speaking each other’s languages. They were doing everything in hand language, which was not unsophisticated. It was quite complex, and they understood what each were doing and negotiating. And you could tell they knew each other and were very familiar with one another, and almost aggressive in the way that they were negotiating, but in a friendly way.

Anyway, I took some photos, and then as he left the shop, I nudged him on the shoulder to see whether he might recognize me, and he looked at me for a minute. Then, a big smile appeared on his face, and he jumped up and gave me a hug. What was cool was like, this guy’s crossing the border from Pakistan into China and still selling stuff the old-fashioned way. It felt like I was witnessing a 1000-year-old tradition of cross border trade, which was amazing.

For those of us who will not physically be able to attend this exhibition, what is the experience of going through it like?

It is arranged in a linear fashion on these photo benches. There are slabs of concrete, which makes it sound ugly, but they are quite attractive. They have a photo with a sort of billboard attached to it. There are 24 of them, so there are 48 sides in total, and they’re arranged in a linear fashion in Granary Square in Kings Cross in London. This is part of the redevelopment of Kings Cross. It’s this beautiful square, a real destination. The largest arts and fashion school is on that square, and the Aga Khan Center, where my office is, is behind that.

These photo benches are arranged in a U shape. Then, there are little dots between them to show you the route so that you can follow it and walk through Europe and into Turkey, into the Middle East, and on into Central Asia and South Asia, and then finally China. So, there’s a clear route, and you can start at either end. There are captions, obviously photographs, and QR codes on each that you can scan. Those are shaped like Islamic geometric stars and will bring up the website we created, where you can access more information about the exhibition, as well as more stories.

I took about 50,000 photographs on that journey and had to distill that to about 160 for the exhibition. So, you can imagine the agony of not including lots of photographs. So, I directed the building of a website that would contain lots of stories and additional content. If you see one thing you liked, you can scan this QR code and access a lot more about it. And we’ll keep adding to that.

Ideally, I’d love for this to become a resource over time of travel, writing, and photography that other people can contribute to as well. We still have 40 unpublished stories, at least.

Why did you choose to travel overland instead of being able to potentially cover more territory by plane?

I guess there were two reasons. One was that—I’ve said this a few times, and I’m never quite sure if it lands, so maybe I’m not really communicating it well—but when you fly to Istanbul, you fly to Tashkent, you fly whatever, you just land in this place. Everything is so fundamentally different, and it’s a quite daunting experience. I mean, it’s thrilling as well. But I wanted to go overland because I wanted something else—I wanted to literally leave the UK by train on the Eurostar to Paris and continue along that way, because I wanted to feel what it’s like to move between cultures and to experience the transitions between them.

I remember when I was in Bosnia and Herzegovina and that was the first time that I heard the call to prayer. As you move, suddenly that becomes a thing. Whereas when you in land in Turkey, of course, it’s present because that’s just the way it is, but when you suddenly hear it for the first time, you’re like, wow, I am moving east. I’m moving into the Islamic world.

You feel these different religions, different influences, coming about as you move from one place to the next. I wanted to feel that personally, but also to document some of that and to tell stories about those transitions. I wanted to see where we borrow from each other and the similarities along the route, both historically and today.

Do you have a single favorite photo from the trip, and if so, what is the story behind it?

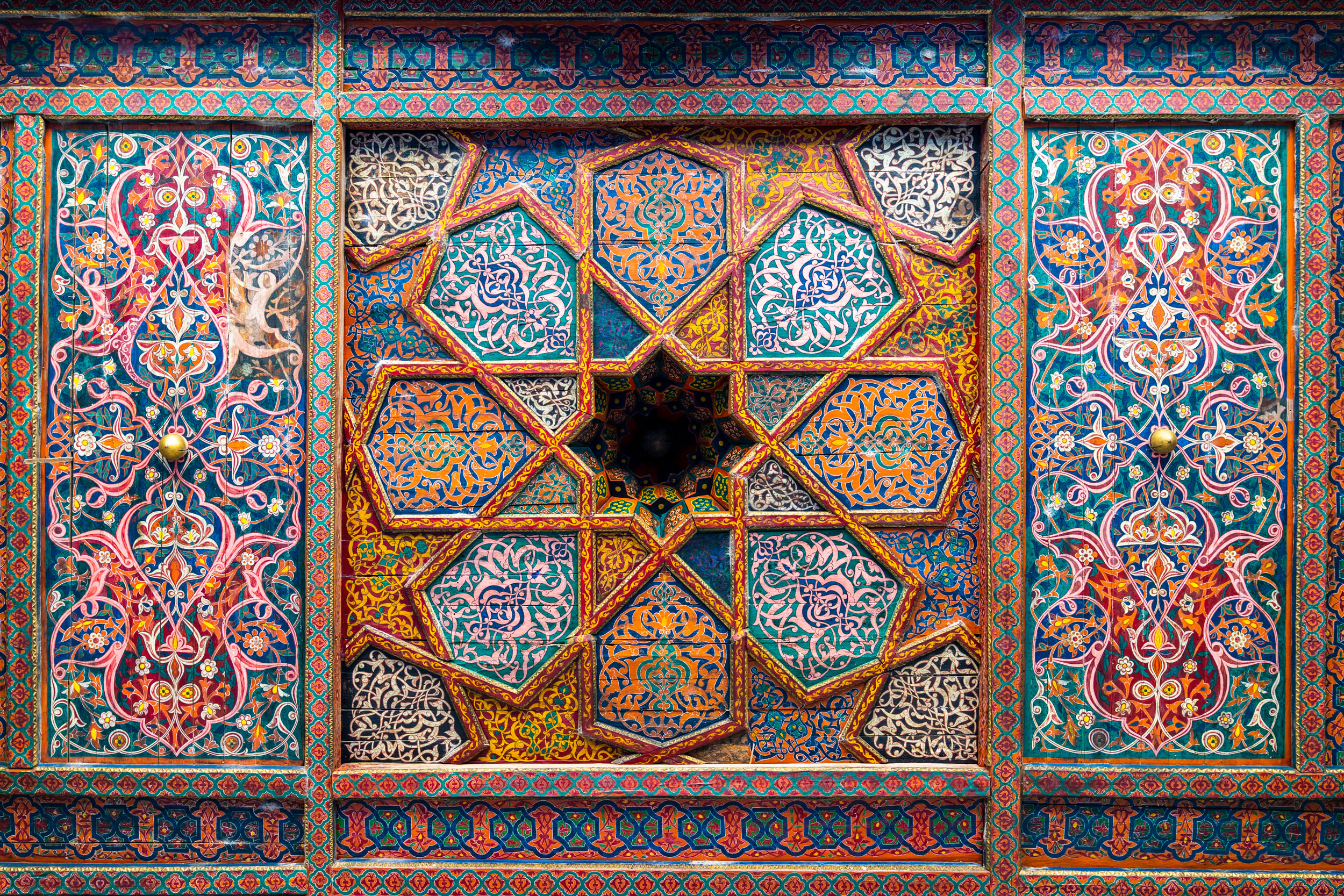

I did this whole series on ceilings of Uzbekistan and ceilings of Iran. There’s one from Uzbekistan, I think it’s the first image on that page on my website. It’s a red ceiling and just so beautiful. It’s a mixture of different styles. You’ve got that Islamic geometry there, but you’ve also got that Central Asian floral decorative motif and that red color.

But I’m just somebody documenting somebody else’s beautiful stuff. You know what I mean? Like, I didn’t make that ceiling. So, from a photographic point of view, it’s probably not that interesting, but as a visual, it’s nice.

There’s one in Tajikistan of this girl dancing. She’s wearing traditional Tajik dress. I remember, when I saw her, I thought, right, I need to get her away from all these other people, because it was at the opening of this tourism center that the Aga Khan Foundation has supported to help drive tourism, international tourism, to eastern Tajikistan, and she was there with a bunch of others. I said, can you come with me? I framed her up in the landscape and then said to her, would you mind doing some of the dancing you were doing earlier, and I’ll photograph you?

That one photograph gets used a lot. I notice other people like it as well because it’s a joyful photograph. It’s showing somebody in a slightly surreal landscape for most people, and she’s wearing this beautiful dress, something people haven’t seen before. So, that one I was a bit more involved as a photographer in terms of the craft of it, and it’s always been a favorite of mine.

You have a talent for capturing architecture—for example, your series on the ceilings of monuments in Uzbekistan. What’s your process for capturing those images?

Just by background, I studied art history and architectural history at university. So, I always loved architecture and art. Architecture is a manifestation of a culture in a time and tells a story about that.

I’d like to say I spend a lot of time considering light and all this, but really, I’m being quite opportunistic. Whenever I’m there, I’m going to try and capture it.

In terms of framing, it is easy to photograph something, and your camera is tilted up or tilted down, and that makes it so that the lines are not straight. So, it’s just about making sure that you’re looking at stuff as flat on as you can. I’m the annoying guy who is trying to get exactly in the middle of everything.

And to be honest, I take a lot of photographs, and then crop and straighten them up afterwards. I’ll do all that because it gives pleasure to the eye to look at something that’s well framed with good proportions, where the lines are straight and the cropping is good. So, I spent a lot of time afterwards making sure that they look as clean as they can.

The places that you traveled were all connected by this historical trade route. What evidence of that remains today?

In Venice, for example, you see quite a lot of this sort of early Orientalism in the architecture. People say that in St. Mark’s Square, St. Mark’s Cathedral, for example, the top of the domes, they echo a little bit like the minarets that the Mamluks built in Cairo, and they had strong trading networks. So, you can see how that would be the case.

Also, on the Doge’s Palace, you have tilework that looks like lozenges, and it’s all over the surface of it. That’s very unusual in Western architecture. And again, one of the theories is that this came from Ilkhanid architecture from Central Asia, with those beautiful turquoise tiles. Sometimes it has that Kufic calligraphy, or sometimes it’s just like chevrons and things like that.

There is the Grand Bazaar of Istanbul, which is obviously still in full throng. I think, pre-COVID, like 90 million people pass through that every year, and it’s not just a tourist thing. Locals shop there as well. That was built as part of the Silk Road, in the later era of the Silk Road, as an engine of Ottoman trade. There are quite a few caravanserais across Turkey that remain. I’m sure some have just disappeared, but some of them, you go in and you can still have a drink there. You can go and have tea. Some of them have been converted into modern day hotels, which is pretty cool. That heritage is still alive today.

In Kashgar, the bazaar is still very vibrant. It’s modern looking, not how it looked 400 years ago, but it’s probably on the same site at least. The bazaars in Tabriz or in Isfahan are very much buzzing, as is the one in Tehran, I think. Those date back a long time. In the 13th century, Marco Polo stayed in Tabriz, which has 22 caravanserais still in it. It has the biggest covered marketplace in the world, an incredible place, and that’s still thriving. So, it’s great to see that department stores and Amazon haven’t completely…not that Amazon would be allowed into Iran…but the equivalent hasn’t completely eroded the way that people shop and engage with each other, as they have done for centuries.

Apart from architecture, what other types of scenes would you say that you’re drawn to, and how would you describe your particular aesthetic?

I always love taking pictures of people. That’s a totally different process because I don’t want to shoot people from a distance or stealthily shoot them. If I’m far enough away, and it’s just their silhouette or something that looks good in the composition, that’s fine. Usually, I like to go do portraits with people, and it’s a nice way of engaging with them. But I need to feel confident. I need to feel good that day to do it, and some days, I just don’t feel like it. But it’s so rewarding being able to have that engagement, look somebody in the eye, show that you’re interested in what they’re doing. Often, I’ll just sit around people for a while, make them feel a bit more comfortable with who I am without taking any pictures, and then start. So, I love to take portraits of people, but I need to feel confident when I do it.

Then landscapes. You can’t beat a beautiful landscape.

In terms of my aesthetic, I’m not sure. To be honest, I don’t know how to describe it. I guess my pictures aren’t very flat. They’re quite contrasty and punchy. I don’t even know if I have a style. I process them all in a similar way. I’ll leave it to you to describe the aesthetic, if indeed there is one.

‘The Silk Road: A Living History’ – presented by the Aga Khan Foundation – is on exhibit in Granary Square, London, from 8 April 2021 through 16 June 2021.