Tatarstan’s Paradiplomacy in Central Asia

Access the data referenced in the article here.

In June 2021, President of the Republic of Tatarstan Rustam Minnikhanov visited Uzbekistan and met with his Uzbek counterpart Mirziyoyev. Such visits have become more frequent in the last decade, with Tatar representatives making their way across Central Asia.

While the strengthening of economic ties is often cited as the main reason for such encounters, the head of Tatarstan’s government also carries the age-old function of being an active intermediary between Russia and Central Asia.

Tatarstan has also taken its own course independent of Russia. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, up until the early 2000s, the region carried out proactive foreign policy, building bridges with Muslim-majority countries like Turkey, Iran and Egypt. However, the recentralization of power that took place under Vladimir Putin reduced the region’s autonomy. Tatarstan, with its Turkic and Islamic background, was then reconfigured into its traditional role of playing various functions for Moscow within the wider Muslim and Turkic worlds.

Historically, Tatars have played an important political role for Russia in Central Asia since Tsarist times. During the Russian conquest, they were employed by the Tsarist authorities to act as a bridge between Russia and their fellow Turkic and Muslims that inhabited the region. The role continued during and after the Russian Revolution, with Tatars sent to Turkestan to spread the Marxist gospel. In addition, several of them played a key role in the establishment of educational institutions in the region.

Economic ties have been of key interest to the Muslim region. The latest available figures show a disparate picture in terms of trade turnover between the Russian federal subject and the Central Asian Republics: from Kazakhstan’s $700 million (2019) to Tajikistan’s $12.5 million (2018). It is common for the Tatar president to be surrounded by a business delegation during his visits to the region. Regardless of which country he goes to, a pattern with the same companies emerges, with the truck manufacturer KAMAZ and the oil company Taftneft as Tatarstan’s major assets vying for influence. Other companies that are also brought up frequently include TAIF, KMPO and Kazan Helicopters.

While the economy might be in many cases the objective of Tatarstan’s relationship with Central Asia, the entry point is one of a common culture and history. Tatars share an overarching Turkic origin with Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Turkmen, although they are more closely related to the first two. In addition, there are important populations of Tatars living in Central Asia, mainly in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. This is a feature that is frequently brought up during Minnikhanov’s visits, where he normally meets Tatar communities.

Kazakhstan, Tatarstan’s long-standing partner

Since 2004, when the then Tatar President Mintimer Shaimiev held a meeting in Astana (Nur-Sultan) with Nursultan Nazarbayev, trade turnover between Kazakhstan and Tatarstan has increased from $130 million to $700 million in 2018, with Kazan and Nur-Sultan aiming to reach the symbolic figure of $1 billion. This makes Kazakhstan Tatarstan’s most important commercial partner in the region by a significant margin.

The commercial relationship is not only one where goods are exchanged. Tatarstan has carried out important investments in Kazakhstan, building two factories in Kostanai to produce components for KAMAZ and a further tyre plant in Karaganda. The importance for Tatarstan of such ventures became apparent when Minnikhanov personally attended the inauguration of the construction works of these factories in 2020 and 2021.

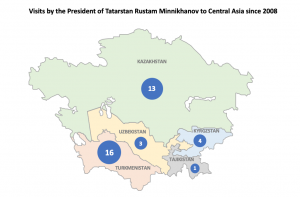

Since taking over the Tatar presidency in 2010, Minnikhanov has visited Kazakhstan at least 13 times. While in some cases he was part of wider Russian delegations, attending different editions of the Russia–Kazakhstan Interregional Cooperation Forum, in most of them he was there to hold bilateral meetings with Nazarbayev and other Kazakh officials.

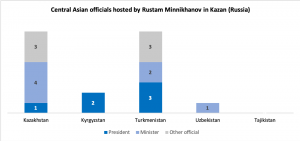

Another aspect that sets Kazakhstan aside for Tatarstan are the visits received by Minnikhanov in Kazan. Since 2010, at least six different high-ranking Kazakh officials have been hosted by the Tatar president in his capital. From Nazarbayev’s own son-in-law Timur Kulibayev in 2012 to the Minister of Information and Social Development last summer. In comparison, Minnikhanov appears to only have publicly hosted one Uzbek minister (in 2017) and two Turkmen officials (in 2010 and 2017), excluding the Turkmen president’s son Serdar. Similarly, he has also hosted Kazakh provincial governors in 2016 and 2018.

During their stay in Kazan, Kazakh officials could have visited Kazakhstan’s consulate, the first Central Asian legation to open in the city in 2013, testament to the importance of bilateral ties.

The strange case of Turkmenistan

While the economy seems to be the clear priority in Kazakhstan’s relationship with Tatarstan, this link becomes more unclear when it comes to Turkmenistan. In economic terms, the size of both Turkmenistan and Tatarstan is similar, with a GDP of $41 billion for the former and a GDP of $35 billion for the latter in 2018 (last year the World Bank published data for Turkmenistan). However, their trade turnover was estimated to be just $107 million in 2019, a significant increase from $24 million two years earlier.

Turkmen-Tatar trade is mostly related to the purchase of KAMAZ vehicles and Mi-17 helicopters produced in Kazan, and collaboration with Taftneft and KER-Holding in the oil and gas industries. One would therefore expect for Turkmenistan to fall behind Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in terms of importance for the Tatar president, but the opposite is true.

Since 2008, while still prime minister of Tatarstan, Minnikhanov visited Turkmenistan at least 16 times, mostly on bilateral working visits for meetings with the Turkmen president. In addition, he has hosted Turkmen President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov on three occasions (2012, 2018 and 2019), while also receiving a visit of his son Serdar (2017 and 2020), as well as a separate meeting with him this year as part of the Eurasian Intergovernmental Council. In comparison, Minnikhanov has only played host to two other Central Asian heads of state: Nazarbayev (2018) and Kyrgyzstan’s Almazbek Atambayev (2017). In both cases they only seem to have visited the Tatar capital one time.

The attention paid by Minnikhanov to Turkmenistan and the trade figures indicate that there must be another factor driving the Tatar’s relationship with President Berdymukhamedov. Demographically, the number of Tatars in Turkmenistan is quoted by Minnikhanov to be 15,000, a number significantly lower than in Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan. And while Turkmen make up the largest group of foreign students in Tatarstan, this does not seem to justify the frequency of the encounters.

Here is where Minnikhanov’s role as a Russian government official emerges. While communications between Moscow and Nur-Sultan are generally fluid, the same cannot be said of Ashgabat. It would be possible therefore that Minnikhanov acts as a bridge between Putin and Berdymukhamedov, carrying out a political role Tatars have historically played in the last centuries between Russia and Central Asia. If appearances are to be considered, the Turkmen president does seem to be more at ease when meeting Minnikhanov than when encountering Putin. The fact that in September 2021, during his latest visit to Turkmenistan, the Tatar was awarded the Independence Order speaks of the positive relationship between both leaders and the importance this has for the Turkmen president.

Uzbekistan, a new beginning

The relationship between Tatarstan and Uzbekistan has been representative of that between Moscow and Tashkent. During the rule of Uzbekistan’s first president, Islam Karimov, the interaction between both parties was minimal, despite Tatarstan having a representative office in Tashkent since the early 90s. Karimov’s isolationists policies left little margin for Tatar paradiplomacy. This started to change with President Mirziyoyev’s rise to power in 2016.

The proactive foreign policy encouraged by Mirziyoyev’s government, advocating for closer ties in Central Asia and further afield, has also had an impact on its relationship with Tatarstan. A year after Karimov’s death, Minnikhanov made his first official visit to Uzbekistan, followed by two more trips in 2019 and 2021. An evidence of the closer political relationship is the opening of Uzbekistan’s consulate in Kazan in 2019, coincidentally the same year as Turkmenistan’s.

The strengthening of economic ties seems to be the priority of such encounters. During this year’s visit, it was announced that Tatarstan would finance the construction of an industrial park in Uzbekistan. As of 2020, trade turnover between both parties stood at $157 million, making Uzbekistan Tatarstan’s second largest partner in the region. Uzbekistan’s opening to foreign capital and companies represents an opportunity for Kazan.

Minnikhanov’s visit to Bukhara and Tashkent came at a time when Uzbekistan is still weighing up the benefits of joining the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union as a full member, something that Moscow is keen on. The official press statements published during the Tatar’s trip made no reference to this matter, but it cannot be ruled out in private Minnikhanov and Mirziyoyev discussed the topic.

Still pending is the first visit of an Uzbek president to Kazan to hold bilateral meetings. Minnikhanov has invited Mirziyoyev but whether he accepts the invitation or not will indicate how much he values this new relationship with Tatarstan.

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, minor players

The wider relationship between Russia and Kyrgyzstan has also affected the latter’s links with Tatarsan. The start of Minnikhanov’s presidency coincided with the 2010 revolution in Kyrgyzstan, in which Russia played an indirect role and that saw the ousting of Kurmanbek Bakiyev. Kyrgyz-Tatar relations started with Bakiyev’s successor, Almazbek Atambayev, who was considered as pro-Russian in the tumultuous Kyrgyz political scene. The following Kyrgyz presidents have all met their Tatar counterpart, but the relationship remains modest, with trade turnover standing at around $41 million in 2020. However, this is starting to change as it can be interpreted from Minnikhanov’s visit to Bishkek in November 2021 to participate in the Kyrgyzstan-Tatarstan Business Forum.

While Tatar authorities have a common Turkic background with most Central Asians, the same cannot be said of Tajiks. This lack of ethnic brotherhood, coupled more importantly with the state of the Tajik economy and geographical distance, have meant that Tajikistan is Tatarstan’s least important partner in the region. Trade turnover was a meagre $12.5 million in 2018 and the only relevant bilateral meeting between both leaders took place as recently as 2019.

Tatarstan has increased its contacts with the Central Asian republics since its current president took office in 2010. This has taken a dual approach. On the one hand, by improving the commercial ties between his region and the Centra

l Asian republics, Minnikhanov is playing his role as head of the government of a Russian federal subject by seeking to benefit and open new markets for companies based in Tatarstan. On the other hand, Minnikhanov

has also been seemingly performing his duties as a Russian official close to Moscow by helping to build bridges and mediate with the Central Asian countries when needed. Despite not being a national actor, Tatarstan has become a relevant component of Russia’s wider policy toward Central Asia.

Francisco Olmos is a research fellow of the Foreign Policy Center, London and specializes in Central Asian affairs. Follow him on Twitter @fran__olmos