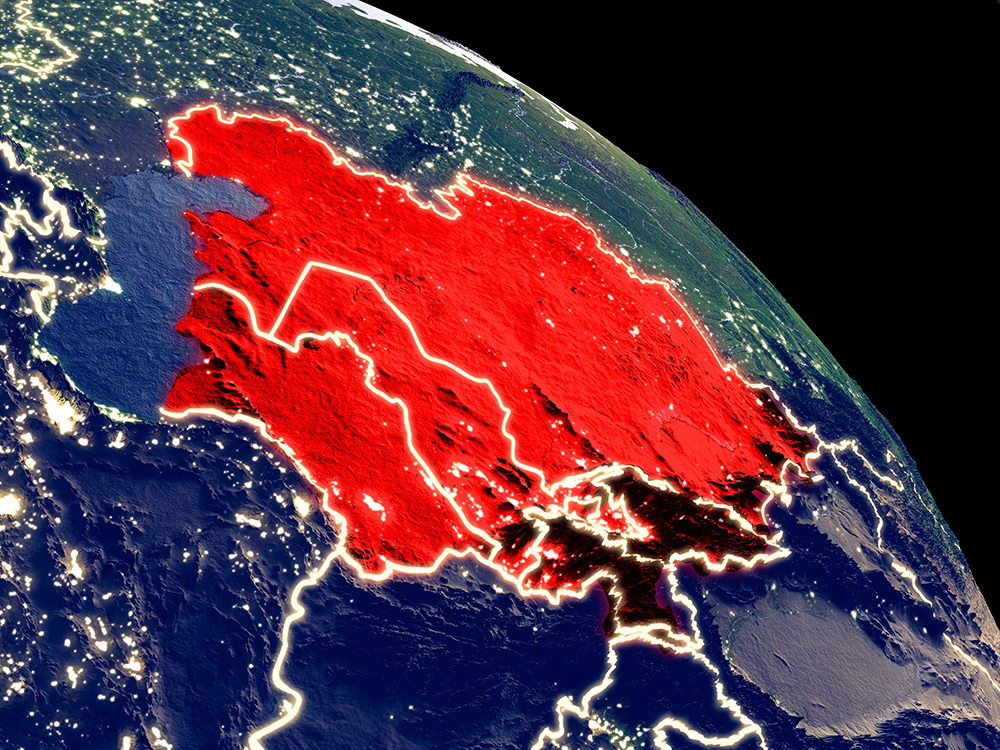

How the War in Ukraine is Hampering Connectivity for Landlocked Central Asia

Throughout its independent history, Central Asia has been restrained in its trade and economic relations with other regions. Despite many attempts by regional countries to overcome this problem, the diversification of transport corridors has not been fully achieved.

Today, the region is substantially dependent on the transport infrastructure going to the north of Eurasia and crossing Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. About 80% of Uzbekistan’s trade transits through Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia and these countries account for 50% of finished products exports from Uzbekistan. In 2021, more than 1 million containers with 23.8 million tons of transit cargo passed through Kazakhstan, indicating that it is advancing its Eurasian transit hub role. However, due to the sanctions against Russia, Belarus and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, these transit corridors are becoming both complex and risky. Alternative shipping routes across the Black Sea have also been compromised by the ongoing Russian naval blockade against Ukrainian ports. Three out of eight major transport corridors connecting Uzbekistan to international markets go through Russia. The Caspian Pipeline Consortium pipeline, which ends in Russia’s port of Novorossiysk, accounts for 80 % of Kazakhstan’s oil exports. Thus, the war in Ukraine is aggravating efforts by Central Asian governments to broaden ties with other neighboring regions and to overcome infrastructural, trade and socio-cultural limitations inherited from their shared Soviet past.

Regional governments have long touted the shortest route to the sea which runs via South Asia. President of Uzbekistan Shavkat Mirziyoyev paid a state visit to Pakistan in March 2022 with shipping routes in mind. The frequency and scope of Uzbekistani-Pakistani high-level meetings increased considerably during the past 5 years, with economic concerns taking precedence over security on the agenda. Earlier in January 2022, the first India-Central Asia summit was organized by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. High-ranking officials from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan visited Iran in February 2022 to discuss using its ports to access global markets. Uzbekistan and other regional countries see South Asia and the Middle East as strategic partners in reaching global sea trade routes and diversifying their foreign political, economic and trade relations.

Recent developments in Afghanistan and Iran have been perceived optimistically in Central Asia. Despite all the shortcomings of Taliban rule, governments are optimistic that their takeover of the country last August could provide stability and security in Afghanistan, which has long hampered connectivity projects. So far, access to Iranian seaports like Bandar Abbas and Chabahar has been limited due to the risks of “secondary sanctions” on firms that conduct certain transactions with Iran. News about the progress in negotiations for the United States to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal should lift the majority of the current sanctions on the Iranian economy. This move would facilitate trade relations with Iran and simplify the railway connection between the countries which opened back in 1996, but has remained underused.

However, there are still many challenges and risks in the improvement of connectivity between Central Asia, the Middle East and South Asia as an alternative to the currently complicated transit via Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.

First, in response to regional diversification efforts, Russia is attempting to strengthen Central Asian dependency on its transit capacity. Trying to avoid diplomatic isolation, Moscow is mobilizing its connections with traditional partners in Central Asia. On April 22, the fifth meeting of foreign ministers of the Russian Federation and the Central Asian nations was held virtually. At the same time, the foreign ministers of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan visited Moscow to conduct bilateral negotiations with their Russian counterparts in March and April. Russia’s deputy prime minister visited Turkmenistan in April and held a presentation of the strategic vectors for the development of the EAEU (Eurasian Economic Union) until 2025 despite the fact that Turkmenistan is not a part of this organization in any capacity. The move may signal Moscow’s desire to involve Turkmenistan within this multilateral format. Furthermore, a May 27 meeting of the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council hosted by Kyrgyzstan was held online with the participation of presidents of member states including Vladimir Putin. Uzbekistan, which is not a member of the EAEU, took part in this summit as an observer country.

Second, the Taliban is still not recognized as the official government of Afghanistan by the international community, which makes it impossible to involve international financial institutions in funding connectivity projects. Important projects within the Central-South Asia connectivity concept are costly and their construction without the engagement of the institutions like the Asia Development Bank and the World Bank is not feasible. Furthermore, the Taliban is now facing both internal rifts and resistance from many competing political groups who are questioning their rule. The internal political situation in Pakistan is also in turmoil after the recent removal of Prime Minister Imran Khan following a no-confidence vote.

The Iranian nuclear deal has not been fully restored yet, despite the potential for a positive outcome in the current negotiations. Anyway, the history of this agreement demonstrates that it can be revised by its signatories when domestic circumstances change. This kind of uncertainty may create additional pressure on the intensification of economic cooperation between Central Asia and Iran.

Given these constraints, Central Asia should make necessary lessons for its future development and conduct a proactive policy of diversifying both its foreign policy and economic cooperation. More active use of the South Caucasus, Iran and China as transit regions may slightly mitigate the existing difficulties for Central Asia. But due to the higher costs and complex politics of using these routes, they cannot replace the traditional transit ways in northern Eurasia. Therefore, these trends require strengthening cooperation in Central Asia and further regional integration to help form a united front.

Akram Umarov is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Center for Governance and Markets, University of Pittsburgh. His research covers security studies, conflict management, public diplomacy and development issues in Central Asia, Afghanistan and CIS countries. Twitter: @umarov_akram