Event Summary: Analysis of the Uzbek Elections

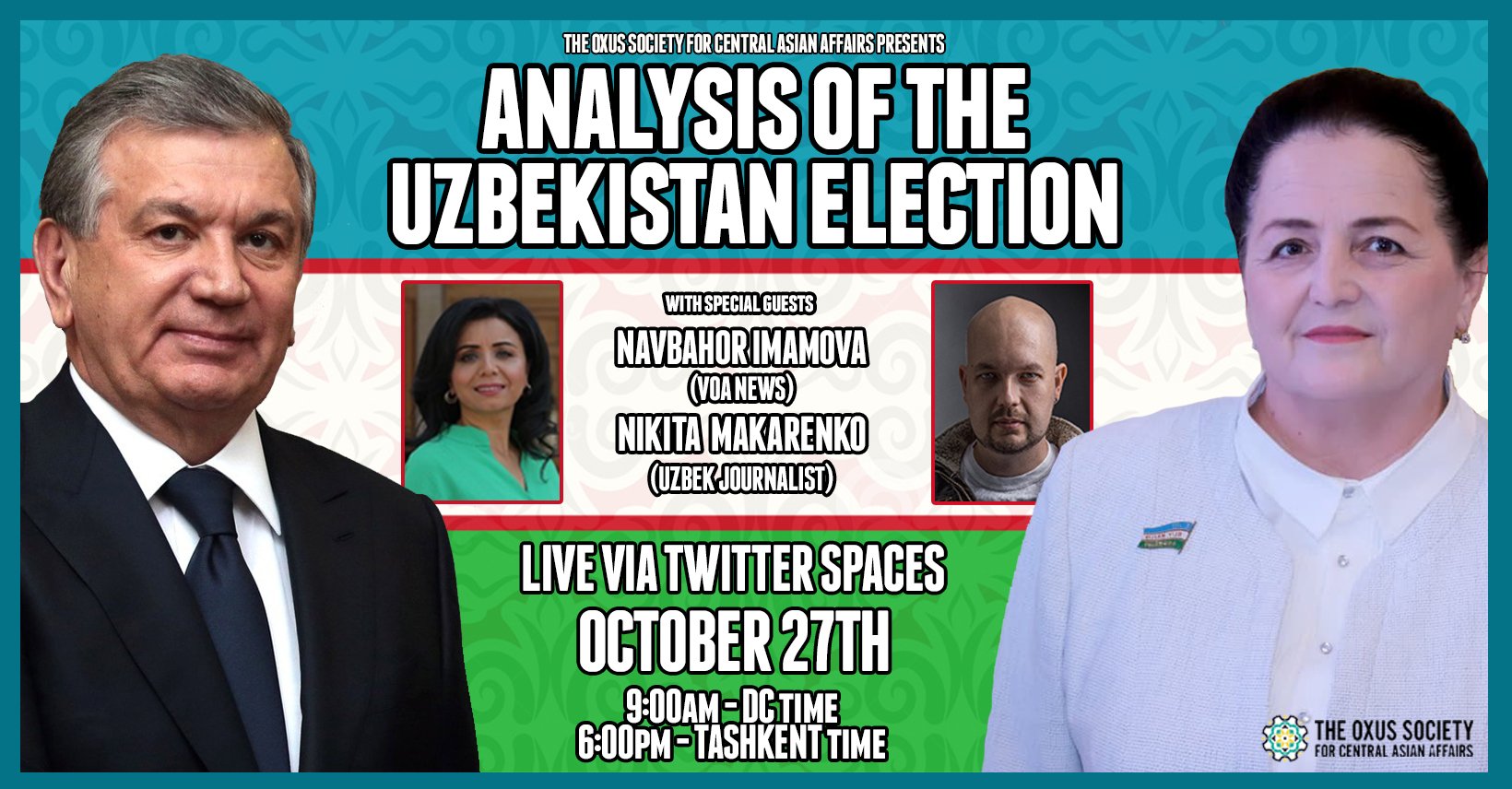

On October 27, the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs hosted a Twitter Spaces discussion about the recent Uzbek presidential election. The event was hosted by Michael Hilliard of Oxus Society’s Spotlight on Central Asia podcast. He was joined by Voice of America’s Navbahor Imamova and Tashkent-based journalist Nikita Makarenko. The irony of having to use VPNs to access Twitter for the duration of the event, with Uzbekistan having blocked the social media site in July, was not lost on anyone.

The October 24 election ended in a resounding victory for incumbent Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who won a second term in office, taking home just over 80% of votes in what both discussants agreed was essentially a non-contest. Discussion largely revolved around what to make of the passionless, formulaic campaigns run by all the candidates, as well as how the election served as a bellwether for Uzbek politics and society as a whole.

When asked whether the result had been a surprise, Makarenko summed up the entire event with an analogy that many of us can perhaps relate to. “You have an uncle which you don’t like, and this uncle doesn’t like you, but you have to visit him on Christmas, and everybody wants to make it as quick as possible.” Navbahor echoed this sentiment, observing that neither candidates nor voters were particularly energized or excited about the elections.

Rather, both discussants remarked on the differences between the 2016 election and this one. Mirziyoyev was initially elected amongst an outpouring of positivity and hope for reform in the country, with voters perhaps too confident in the ability or willingness of the government to meaningfully effect positive changes. The decrease from a 90% winning majority in 2016 to a mere 80% in 2021 is more of a notice that Uzbek society still supports him, even if few were excited about the election. To note a positive change, Navbahor witnessed an increase in participation among families and religious voters. However, the election had also seen continued attempts by heads of families to vote for their entire group.

Candidates were remarkably lethargic in their attempts to court votes, with debates almost farcical in their simplicity, with press briefings sounding like “reports of the Politburo.” Two particular candidates who had been the subject of speculation before the election, Maqsuda Vorisova and Alisher Qodirov, failed to take more than 6 percent of the vote respectively. The larger issue that both discussants highlighted was a lack of ideological engagement from the candidates, stemming in part from a historical lack of organized political opposition.

If Mirziyoyev’s first term in office was dedicated to moving past the ugly shadow of former President Islam Karimov, who ruled the country from 1989 to 2016, then his second term will need to demonstrate renewed reform efforts while successfully navigating growing challenges. Makarenko highlighted that issues of poverty and environmental degradation in particular were becoming unsustainable, even as Uzbekistan became more integrated globally and its eceonomy has developed.

On the flip side, Navbahor attested to a continued interest in regional cooperation and finding ways to seek common ground with neighbors on connectivity projects or even the divisive Afghanistan issue. It is “easy to be cynical,” she said, “how many Silk Roads have we heard about over the years?” Nevertheless, state ambitions for regional and global engagement will remain the center of attention over the next five years.

Looking forward, it remains highly unlikely that new parties or politicians will emerge in time for the 2026 presidential election. The existing parties are by and large inherited from the old regime, but even potential new organizations are drawing from the same pool of politicians and former apparatchiks. If any exciting movements were to have developed, Navbahor claimed they already would have appeared in the heady first years of the Mirziyoyev presidency. As it stands now, there is not an ideological spectrum diverse enough to create political competition or platforms based on actual policy differences.

The one clear projection is that, were Mirziyoyev to attempt to run again (a move not currently legal), it would essentially eradicate all of the goodwill his rhetoric and attempts at reform had engendered. However, neither discussant could rule out that Mirziyoyev wouldn’t remain or simply hand-pick a successor in 2026, and Makarenko was particularly vocal about the almost “spiritual” connection that Uzbek society accords its president. The nature of Mirziyoyev as a “chosen one” was explained as a byproduct of centuries of coming to terms with strong rulers, and Makarenko claimed that it would take not five but 50 years for Uzbeks to be ready to seek more robust, dynamic political representation.

While the election was straightforward, the administration is aware that the country remains at an inflection point. Navbahor articulated that political growth was still possible for any organization or party that could find ways to invest in positive energy and the stirrings of activism among voters. More importantly, she reiterated the simple truth that “if you don’t give people what they want, they will leave.” It remains to be seen whether Uzbekistan’s government can deliver on the promises of reform that its people so desperately crave.

Austen Dowell is a Research Assistant at the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs and a graduate student at the Harriman Institute, Columbia University.