Avoiding Dependence? Central Asian Security in a Multipolar World

By Bradley Jardine and Edward Lemon

In September, the Pentagon published a report listing Tajikistan as one of 12 countries the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) “has likely considered” for military facilities. What the report neglected to mention, is that China’s People’s Armed Police (PAP) has been operating a secretive base named Sitod (“headquarters” in Tajik), near Tajikistan’s border with Afghanistan, since 2016. This is part of China’s growing security footprint in Central Asia.

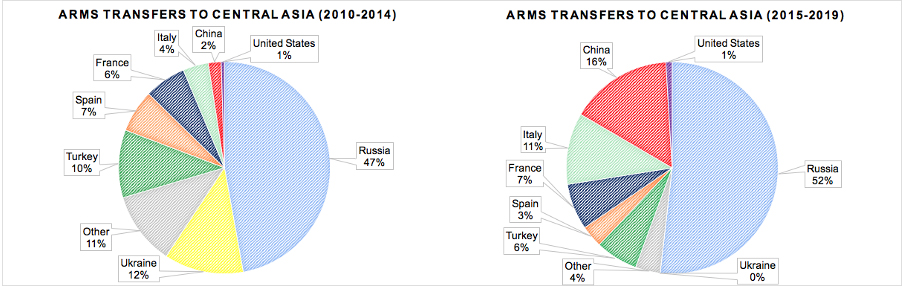

China’s rising presence in this part of the world comes at a time when Russian power is in slow decline. Russia, which accounted for 80 percent of the region’s total trade in the early 1990s ($110 billion), lost the position as the region’s leading trade partner during the global financial crisis in 2008. China’s trade with Central Asia in 2019 was just under $30 billion, one-third higher than Russia. But nevertheless remains the dominant external security provider to the region. Russia has accounted for 52% of the regional arms market over the past five years and maintains substantial military infrastructure in three out of five of the republics.[1]

But this is changing as China makes significant inroads into the security sector. It has provided 13% of the region’s arms over the past five years, a significant increase from the 1.5% of Central Asian arms imports that it provided between 2010 and 2014, according to data collected by the authors of this report. Having opened its first military facility in the region in 2016, it has also begun projecting the operational capabilities of its paramilitary units into the region

Significantly, China has moved away from the traditional multilateral framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which also includes Russia, and created two new regional groupings. It founded the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism (QCCM) with Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan, allowing China to conduct independent border patrols with member states. And in June, China held the first meeting of C+C5, which brought the Chinese foreign ministry together with the five Central Asian states, copying the United States C5+1 initiative.

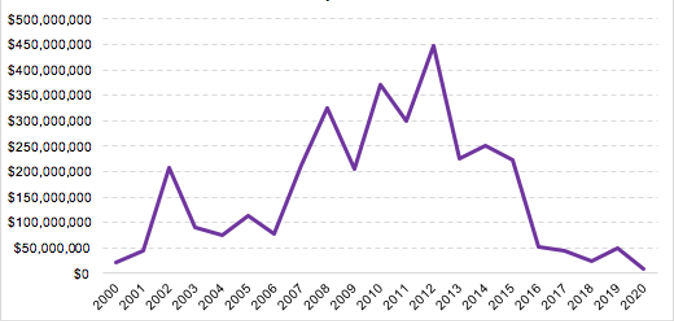

The United States, which at one time had two bases in the region, has dramatically scaled back its security assistance to the region, falling from a high of $450 million a decade ago to just $11 million in 2020. India’s role, meanwhile, remains limited, but is nevertheless growing. Having signed a series of agreements with Central Asia’s militaries, India has gone on to organize nine bilateral exercises since 2015, and has started participating in exercises with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which it joined in 2017.

Being courted by multiple powers is certainly in the interests of the Central Asian states as they strive to avoid dependence on one external power. The Central Asian states have managed to push back against external powers a number of times. Kyrgyzstan’s government bowed to popular pressure to cancel a $275 million Chinese logistics center in February 2020. The Tajik government rejected a Russian offer in May 2020 to mediate its border dispute with Kyrgyzstan, saying it was an “internal matter.” And former Kyrgyz president Kurmanbek Bakiyev tripled the rent for the U.S. base in the country, while promising Moscow he would close it in exchange for $300 million in aid; the U.S. lease was eventually terminated in 2014.

The U.S. is largely exiting the region as a security partner, while Moscow continues to retain a strategic edge over Beijing. But the gap is closing, and, if the trends continue, Moscow may find its influence further undermined in the coming decade.

Arming Central Asia

Arms transfers not only offer an opportunity for domestic arms companies to turn a profit, but also have the potential to create relations of dependence on the supplier for continued upgrades and support. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the new successor states of Central Asia came into possession of vast stockpiles of weapons. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan were left with the largest arsenals. Thanks to this surplus, Central Asia became a net exporter of military equipment in the 1990s, selling some $275 million dollars’ worth of weapons systems between 1991 and 1999 according to the SIPRI Arms Transfers Database. The region in turn imported some $274 million in the same period, primarily from Russia. One of the region’s most significant customers was the People’s Republic of China. In 1998, for example, Beijing purchased over 40 Shkval torpedoes from Kazakhstan.

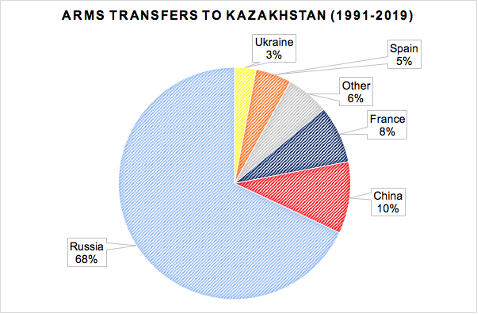

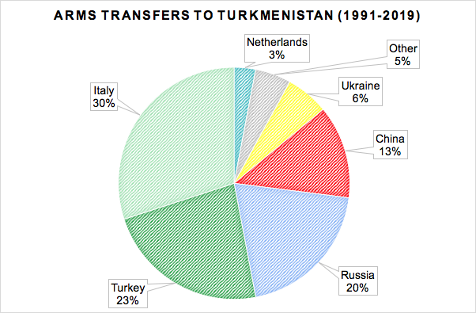

As Soviet-era equipment became outdated and unserviceable, the Central Asian militaries became net importers of arms after the turn of the millennium. The largest of these is Kazakhstan, which accounts for just over half of military imports in the region according to figures assembled for this report. Turkmenistan, which embarked on an ambitious military modernization program in 2016, has accounted for 27% of imports. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are largely reliant on military aid, which is included in our figures.

Russia remains the leading exporter of arms to Central Asia, with its $3.8 billion of exports accounting for just over half of the arms transfers since 1991. Exports in the 1990s were relatively minimal. Peaking at $350 billion in 1988, just before the collapse of the Soviet Union, within the next decade Russia’s military budget would plummet to just $19 billion. But since Putin came to power, the budget has grown substantially again, reaching $47 billion in recent years, or $150 billion if you use PPP. Despite China’s rising role as a security provider in Central Asia, Russia’s market share has actually increased from 47% to 52% over the past decade.

Kazakhstan remains the largest consumer of Russian arms in the region, accounting for 60% of Russian exports. The two countries formed a Unitary Regional Air-Defense System in 2013. In exchange, Kazakhstan received the S-300PS air-defense system free of charge. Most recently, Russia supplied the Kazakh navy with two minesweepers, four Mi-35M attack helicopters and 12 Su-30SM fighter-bombers. Kazakhstan has also prioritized the development of its own defense industry, signing an agreement with Russia in 2019 to assemble Mi-8AMT and Mi-171 helicopters within its borders.

Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan remain the most dependent on Moscow, with 97% and 76% reliance respectively. In the case of Tajikistan, noted Russian defense experts have long referred to the country as an “outpost” of the Russian army. Dushanbe received over $122 million in Russian arms in 2019, with a further $200 million earmarked for the modernization of the Tajik army up to 2025. Kyrgyzstan has also benefited from Russian military aid. In 2012, the Russian military offered Bishkek a $1.1 billion aid package to modernize its forces. Since then, Moscow has supplied over $200 million worth of second-hand weapons and gear to the Central Asian republic.

Despite lukewarm relations, Uzbekistan has received 59% of its arms from Russia since independence. And since the death of long-time strongman Islam Karimov in 2016, Russia has only expanded its influence over the country’s military. By 2018, Tashkent’s military spending had swollen to $1.4 billion, with a flurry of deals signed with Moscow guaranteeing 12 Mi8 attack helicopters, armored personnel vehicles, and Su-30SM fighter jets.

Like Uzbekistan, neutral Turkmenistan has attempted to decouple its security from Russia. It has the most diversified portfolio of arms suppliers in the region. While Russia has sold more weapons to Turkmenistan than China, with $370 million of sales compared with $234 million from China, it is still not Turkmenistan’s largest arms supplier. Italy, having signed a deal to provide for five AgustaWestland AW-139 helicopters in 2011 and signing a mammoth deal worth over $500 million in 2019, which seems to have been for Aermacchi M-346 jets.[2] The 2019 deal skews the arms transfers figures in Italy’s favor. Turkmenistan’s second largest supplier is Turkey, which has supplied $407 million to Turkmenistan, according to the SIPRI database, including patrol ships and armored personnel carriers.

China has become a more active arms supplier in recent years, exporting some $15.7 billion worth of weapons to countries around the world between 2008 and 2018. Central Asia has been no exception, but in recent years Chinese supplies have grown exponentially. Until 2014, China’s exports were limited to light weapons, small-scale military aid and non-lethal supplies, such as gas cylinders and uniforms. China accounted for just 1.5% of arms transfers to the region between 2010 and 2014. In the past five years, China has dramatically ramped up exports, capturing 13% of the market. In 2018, Turkmenistan purchased portable surface-to-air missiles from China. That same year, Kazakhstan purchased eight Chinese Y-8 transport aircraft. Chinese suppliers also provided Tajikistan with VP11 patrol vehicles and cutting-edge Snow Wolf High Mobility Special All-Terrain Vehicles.

Arms transfer from the United States to Central Asia, meanwhile, have been negligible. With just $80 million transferred since 1991, it accounts for just 1% of transfers, falling far behind a number of other NATO-members, including Italy, the region’s second largest supplier with $1.1 billion, Turkey ($425 million), France ($397 million) and Spain ($252 million). The single biggest transfer, 300 used Mine-Resistant Armor-Protected (MRAP) vehicles worth $35 million, came after the lifting of sanctions against Uzbekistan in 2015.

As Figure 4 indicates, U.S. security assistance, which includes arms transfers, training and capacity building, peaked at almost $450 million in 2012 in the run up to the planned scaleback of operations in Afghanistan. But since then assistance has fallen, reaching a two-decade low of just under $10 million in 2020, a 98% fall in funding.

Bases, Exercises and Training

China, the United States and Russia are united in their concern over the potential for spillovers from Afghanistan, which shares a 1,432 mile border with post-Soviet Central Asia, and the need to maintain stability in the region. The United States opened two bases in the region after 9/11 to support its war effort in Afghanistan. Russian officials repeatedly warn of the potential for terrorist groups, in particular the Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP), moving north and threatening regional security. China seems to share this concern. In last year’s leaked “Xinjiang Papers,” it was revealed that Chinese President Xi Jinping has been paying close attention to Central Asia. “After the United States pulls out of Afghanistan, terrorist organizations positioned on the frontiers of Afghanistan and Pakistan may quickly infiltrate into Central Asia,” he said in a series of secret speeches issued in 2014. Russia had border guards stationed on the Turkmen-Afghan border until 1999 and on the Tajik-Afghan border until 2004.

Russia maintains significant strategic facilities in Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. It remains the non-Central Asian state with by far the most personnel and equipment deployed in the region. Concerned over possible spillovers from Afghanistan, China established its first military facility in Tajikistan in 2016, 14 kilometers from the Afghan border. Satellite images suggest the base is equipped with heliports and enough barracks to house a battalion with the support of armoured vehicles. That same year, China’s Jing’an Import and Export Corporation helped build a new anti-drug trafficking building in the town of Kulob and has installed sensors on Tajikistan’s borders. In addition, China provided Dushanbe with a grant of $19 million to build officers’ clubs.

Following 9/11, Russia agreed to a U.S. plan to place troops in Central Asia to aid its invasion of Afghanistan. The U.S. opened bases in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, with the Manas Airbase just outside of Kyrgyzstan’s capital city becoming the transit point for all U.S. soldiers arriving in Afghanistan. But in 2005, Uzbekistan closed the American base in the country in response to Washington’s criticism of the Andijan massacre, a bloody crackdown on protesters in which Karimov’s troops reportedly killed more than 700 people. The situation in neighboring Kyrgyzstan was no better; it terminated America’s lease on the Manas Airbase in 2013, following pressure from Russia. France opened a small logistics base in Tajikistan in 2002. But it was shuttered in 2013. And Germany’s base in southern Uzbekistan, which had provided support to NATO troops in Afghanistan, closed in 2015.

India’s attempts to establish a base in the region have come to no avail. In 1997, India agreed to renovate the Farkhor Airbase in southern Tajikistan, stationing medical personnel there. When Northern Alliance leader Ahmed Shah Masood was attacked just two days before 9/11, he was rushed to the Tajik hospital there, where he was pronounced dead. Yet India has never stationed troops or military aircraft at the base. A second object of Indian interest in Tajikistan has been the Aini Airbase. Between 2002 and 2010, India spent approximately U.S.$70 million to renovate the airbase with the hope to station military aircraft there. But it appears that Russia blocked this attempt.

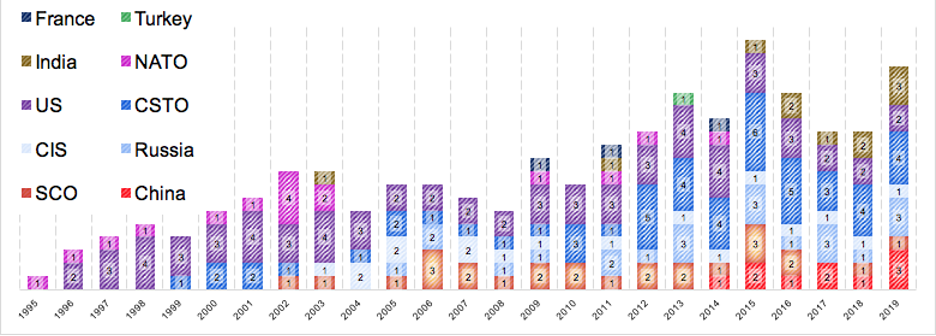

Central Asian militaries have been involved in at least 227 joint exercises with non-Central Asian states since independence. Russia, and Russian-led organizations, including the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) have organized 91 of these exercises. The U.S. and NATO have organized 85 of these exercises. And China, bilaterally or through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, has organized 36.

Russia, the U.S and China rely on a mix of bilateral and multilateral exercises organized under the auspices of their respective regional organizations: NATO in the case of the U.S., the SCO in the case of China; and the CSTO and CIS in the case of Russia. As Figure 5 indicates, military exercises have become more frequent in the region, peaking at 18 in 2015. Russia still conducts most of its exercises through the CSTO. Russia also holds bilateral exercises, usually through its facilities in the region. Notably in 2017, Russia held its first exercise with Uzbekistan in 12 years at the Forish range in Jizzakh, the site of the two countries’ only previous bilateral exercise in 2005.

NATO was the first organization to hold a joint exercise involving the Central Asian militaries in 1995. Cooperative Nugget brought together 4,200 troops from the U.S., Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan together for a peacekeeping exercise in Fort Polk, Louisiana. NATO exercises emphasized interoperability with NATO and Partnership for Peace members, a program in which all five Central Asian states participate. Exercises involving NATO peaked in 2002 in the aftermath of the invasion of Afghanistan with four exercises held. Since then, they have steadily declined, with the only regular exercise since 2014 being the Steppe Eagle, between Kazakhstan, the United Kingdom and the United States. U.S. exercises peaked after the invasion of Afghanistan and again in 2013 in the run up to the planned NATO drawback. But like security assistance, U.S. training exercises have also dwindled with Regional Cooperation the only exercise involving Central Asian militaries since 2016.

China has also moved away from conducting exercises through multilateral frameworks such as the SCO and toward bilateral cooperation. In 2002, China launched its first ever bilateral training exercise when it held joint exercises in Kyrgyzstan. These would increase dramatically in number after 2014, with at least ten bilateral exercises taking place. In 2015, Chinese special forces units joined their Tajik counterparts for a series of counterterrorism exercises outside Dushanbe. This was the first time that the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) special operations forces conducted training exercises overseas. The exercises lasted two days and involved over one hundred Chinese personnel. Coordination 2016 involved four days of counterterrorism exercises on the Afghan-Tajik border in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region with a small mobile company of 414 PLA troops joined by a large contingent of Tajik troops, numbering up to ten thousand. Another joint exercise involving a PLA company in Gorno-Badakhshan was held in August 2019. In October 2019, China and Kazakhstan conducted their Fox Hunting-2019 counter-terror drills at a training camp in Ust-Kamenogorsk, Kazakhstan with the participation of the PLA.

In August 2019, Kyrgyz soldiers joined their Chinese counterparts in Xinjiang to take part in their Cooperation-2019 counter-terror drills. This series of drills has been conducted across the region and aims to enhance the interoperability of local paramilitary units with the People’s Armed Police (PAP). These were the first drills in which the Kyrgyz National Guard and the PAP have worked together. In May 2019, The Uzbek National Guard and the Chinese People’s Armed Police conducted two-week-long joint anti-terror exercises as part of this series at the Forish field-training base in Uzbekistan’s Jizzakh region. Tajikistan also participated in China’s Cooperation-2019 drills last August.

In recent years, India has become more active in cooperating with militaries in Central Asia, organizing 11 exercises, nine of which came in the past five years. India held its first military exercise in Tajikistan in 2003, at the time it was trying to establish an airbase in Aini. Another exercise with Kyrgyzstan followed in 2011. Kanzhar-2011 involved just 20 troops from Kyrgyzstan. But since 2015, India has ramped up its activities in the region, organizing five further exercises with Kyrgyzstan, holding the KAZIND exercises with Kazakhstan annually since 2018 and a first exercise with Uzbekistan in 2019. But these exercises seem to be largely for show, with fewer than 100 personnel involved in each.

Conclusion

With the United States gradually exiting the region and Russia’s role slowly declining, China looks set to play a growing role in Central Asia’s security. But Central Asia’s governments and people are not mere pawns in a game of Xiangqi. They have their own agendas and will look to capitalize on growing multipolarity, which could benefit their own attempts at avoiding overreliance on one external partner.

Central Asia’s governments, in particular Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, have to reckon with persistent Sinophobia among segments of their population. Opinion polls in the region indicate that while Russia is still viewed favorably by many Central Asians, China is viewed with greater suspicion, with 30% of Kazakhs and 35% of Kyrgyz polled reporting negative views of their eastern neighbor. As part of the Central Asia Protest Tracker (CAPT) project, the Oxus Society found 97 anti-China protests in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan between January 2018 and August 2020. Protests targeted Chinese investment, particularly in the extractive industries, or China’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang, where over a million ethnic Kyrgyz and Kazakhs reside. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi singled out Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in a recent tour of the region, pledging to support both as they manage the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

China’s rise in the region is neither easy, or inevitable. While its economic clout has given it powerful political inroads, local skepticism will continue to put a check on China’s ambitions. At present, Chinese officials will continue with their business as usual “warm politics, cold public” approach to the region by largely abstaining from political debates. But as backlash against China continues, Beijing will continue to perceive its interests to be at risk and seek to protect its investments, bringing the potential for more push back in a vicious cycle. If it does not change tack by designing projects that provide genuine benefits for local people rather than the elite and taking public diplomacy more seriously, Beijing may find itself faced with a downward spiral of dissent outside its Western frontier.

[1] For this report, our figures were drawn from the SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, supplemented with EU arms export reports, government documents, The Military Balance and local media reports. These figures include provision of military goods and services, and do not include the sale of licenses to produce arms domestically.

[2] “Turkmenistan Presumed to be M-346 Customer,” Defense and Security Monitor, 26 May 2020, https://dsm.forecastinternational.com/wordpress/2020/05/26/turkmenistan-presumed-to-be-m-346-customer/