Understanding Disorder in Central Asia

A Joint Report by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) and the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs

The five countries in Central Asia — Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan — all display varying degrees of authoritarian rule. Across the region, local economies are stymied by corruption, resulting in a dissatisfied and increasingly vocal populace (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 18 October 2019). In two of the republics, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, election-related demonstrations have altered the political landscape, but across the board, state directed-force and mob brutality are rife.

This report builds on a burgeoning partnership between the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) and the Oxus Society’s new Central Asia Protest Tracker (CAPT). While the two datasets were designed to tackle different research questions, the data they provide and the trends that they highlight are complementary, allowing users to gain an even broader understanding of political dynamics in the region.

Introduction to ACLED

ACLED is a disaggregated data collection, analysis, and crisis mapping project tracking disorder, which includes political violence, demonstrations, and strategic developments. Information is tracked around the world in real-time, collecting information on the dates, actors, locations, fatalities, and types of events that take place. The ACLED project’s methodology covers a range of events types, including battles, explosions/remote violence, violence against civilians, protests, riots, and strategic developments. These event types are further disaggregated into sub-event types for a more granular analysis of disorder. In addition to information on actors involved in events, the type of agent is also captured to track broader shifts in patterns of disorder.

In addition to data collection, the ACLED team conducts analysis to describe, explore, and test conflict scenarios, with analysis made freely available to the public. ACLED’s analysis is developed from extensive academic research into the dynamics of political violence across the world and specific case studies of conflict agents, local trends, and intersections with domestic political contexts. ACLED analysis is unique due to its intersection between theoretically informed frameworks and hypotheses with local-level empirical data and analysis.

While ACLED is a United States-based non-governmental organization with a 501(c)(3) designation, it is a fully remote organization, with researchers based around the world. Such a system allows for researchers to be based in or have connections to the countries that they cover, benefitting from local language and context knowledge. ACLED data rely on a number of sources,[1] including traditional news media, with local news sources prioritized; civil society organizations; local partners, such as local conflict observatories and organizations tracking certain political violence or protest trends in specific contexts; and select ‘new media’ sources. Given the restrictions on the free press in the region, trusted new media sources are used to expand coverage, especially for rural events where they help to capture local, small-scale protests and mob events. ACLED does not crowdsource information. New media relied upon in the Central Asian region includes broadcasting services reporting through videos posted to online forums, Facebook pages of local political groups, and Twitter accounts of prominent politicians and specialists of the region, for example. A targeted approach to the inclusion of new media in Central Asia has been adopted by ACLED, as all sources are verified for reliability and only reports with clear information on location, actor, and date are coded. This overarching sourcing strategy allows for the production of locally informed data, which are the cornerstone of ACLED’s methodology. This approach sets ACLED apart from other global conflict datasets in critical ways.

The ACLED dataset is hence built on the notion that all countries experience some forms of disorder, and that the modality of that disorder is strongly shaped by the specific vulnerabilities, political fault lines, and priorities of each society. Waning institutional trust and strength, income inequality, and demographics can all be sources of disorder, contributing to both demonstrations as well as political violence. Protest movements and government response to demonstrators can result in the birth of violent actors engaging in conflict, and ongoing conflicts can fuel protests involving affected populations, for example. This is why ACLED seeks to capture this spectrum of disorder, especially given that disorder does not present as the same in every space. An expansive view of its modalities allows for an accurate account of the occurrence and patterns of disorder across countries as diverse as those in Central Asia in comparison to those in Africa or Latin America, for example. ACLED hence relies upon a standardized methodology to capture the spectrum of disorder around the world, while weighing methodological decisions whenever expanding coverage to new geographic regions. (For example, specific methodological decisions taken into account for Central Asia are described in this primer.)

ACLED’s Central Asian coverage dates back to the beginning of 2018, and as of the end of 2020 includes 2,874 events capturing demonstrations, political violence, and strategic developments, including 1,589 in Kazakhstan, 814 in Kyrgyzstan, 336 in Uzbekistan, 97 in Tajikistan, and 38 in Turkmenistan. This information comes from over 130 unique sources. Data are updated weekly by experienced researchers who review traditional media in Kazakh, Tajik, Turkmen, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Russian, and English languages.

Introduction to Oxus Society’s CAPT

The Central Asia Protest Tracker (CAPT) is an original dataset of protest events compiled by the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs. It describes and categorizes protest activity in each of the five Central Asian republics from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2020 with future updates to be scheduled on a quarterly basis. Currently, the Central Asia Protest Tracker records 1,577 protest events, including 780 in Kazakhstan, 603 in Kyrgyzstan, 147 in Uzbekistan, 29 in Tajikistan, and 18 in Turkmenistan. The dataset provides a useful analytical tool for the study of local protest dynamics and the issues which prove to be of most importance to the peoples of the region. In addition to issue sets, the data also offer insight into common targets of dissent, whether it is local or national governments, businesses, or law enforcement — to name a few, as well as the responses made by targeted institutions, ranging from the use of force to accommodating protester demands.[2]

The CAPT database consists of online published material that is public and identifiable, but not private. The use of online source material allows Oxus Society to cross-check data and conduct follow-up studies, for example, by reaching out to activists involved in specific protests to inquire about whether their activities led to substantial policy change. Due to the nature of the collected data, the dataset is likely to have a substantial effect on the results of empirical research. Reliance on reporting means that many cases of activism not considered “newsworthy,” or that took place in geographically remote communities, may be missing from the final results, skewing findings. While the CAPT does attempt to address this by mining social media platforms for additional sources of data, these sources also come with their own issues of verification and many unreported protests are likely missing from the dataset. The CAPT dataset uses ACLED entries to supplement its own data gathering by identifying issue cases; the research team searches corresponding reporting from the incidents to verify events and data according to CAPT coding standards.

The CAPT uses 28 categories of issue type ranging from environmental protests to pro-government demonstrations, while also coding for 9 types of target (e.g. national government, security services, foreign businesses). This degree of coding allows for a much more granular approach to understanding protest dynamics and the issues which are mobilizing Central Asians on the streets.

Both ACLED and CAPT rely on a geospatial definition of dissent, which leaves out important activities like online protests, petitions, and types of resistance that do not require citizens taking to the streets. This narrow definition of dissent therefore skews the results, with important forms of subtle dissent and online campaigns left out of the analysis.

Complementarity of the Data Projects

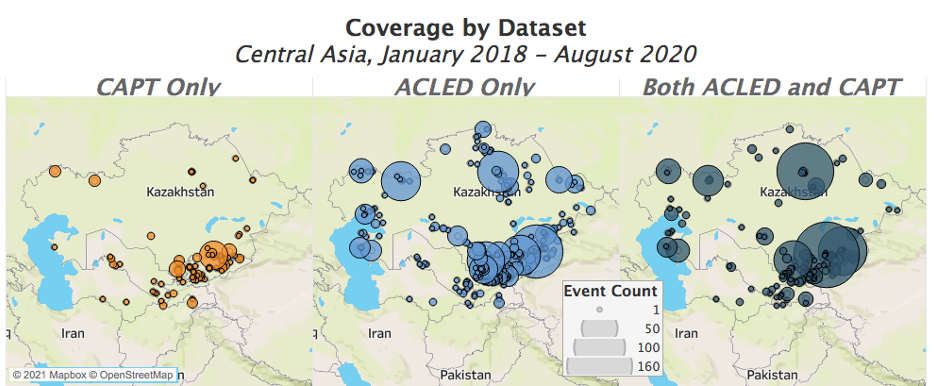

Given the data coverage and mandates of these projects, the picture of Central Asia that emerges based on data from the two is complementary, with patterns of overlap and distinction between the two. The maps below depict this overlap by matching events across the two datasets. In addition to the CAPT events which cite ACLED explicitly, there is also overlap in coverage across other events as well — those events which both datasets coded based off of similar sources, for example. In order to ensure an accurate reflection of the overlap, such events have also been matched. Events colored in navy are those which both organizations report. Events in blue are those which ACLED alone reports; this includes some protests, as well as incidents of political violence, including communal violence, state repression, and mob violence, which fall outside of CAPT’s threshold for inclusion. Events in orange are those which CAPT alone reports, which are largely small-scale acts of protest, like self immolations or individual-person demonstrations; these events fall outside of ACLED’s threshold for inclusion, which identifies protests as groups of three or more people physically congregating together.[3]

Spotlights

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan is a multi-ethnic country, though ethnic Kazakhs constitute the majority of the population (Eurasianet, 21 February 2020). Violence targeting ethnic and religious minorities occasionally takes place, although most remain small in scale. In addition, xenophobia persists, mostly directed towards Chinese workers in the country as part of a larger reaction to China’s economic dominance in the region. China invests in large infrastructure projects and mines in the country, triggering anxiety about financial dependence on Beijing (The Jamestown Foundation, 10 September 2019). China’s harsh policy course in its culturally contiguous Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), which involves mass internment camps targeting Muslim minorities — including ethnic Kazakhs — has only exarcerbated anti-Chinese sentiments among broad segments of the population.

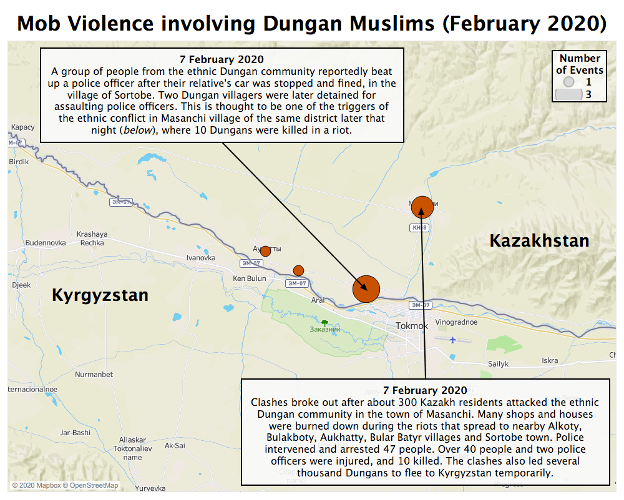

In February 2020, ACLED tracked violence that broke out between members of the Dungan Muslim ethnic group and Kazakh villagers in Kazakhstan’s southern Zhambyl region (see map below based on ACLED data). While reports vary on what exactly triggered the event, the dominant view is that a video circulated on social media purportedly showing a fight between Dungans and police officers, leading to several hundred people demonstrating in Masanchi and nearby villages, mostly populated by the Dungan community (Eurasianet, 10 February 2020). A number of people were killed, with numerous injuries and cases of hospitalization for police officers and civilians alike. Multiple houses and shops belonging to Dungans were damaged. The incident also led to the temporary displacement of hundreds of Dungans to neighboring Kyrgyzstan (RFE/RL, 10 February 2020). These were the deadliest ethnic clashes reported in Kazakhstan in recent years, and reveal that minorities continue to experience discrimination in the country. In response, the government dismissed the regional police chief, the regional governor, and the district governor.[4] Both this violence as well as the associated demonstrations can be seen in the map below based on ACLED data.

According to data gathered by the CAPT, Kazakhstan has recorded the highest number of China-related protests in the region, with at least 63 events between January 2018 and December 2020. Protests stem from concerns that Chinese investors will take land and jobs from Kazakhs, or oppose China’s policies towards its Muslim population in Xinjiang, where one million ethnic Kazakhs reside. For example, on 3 September 2019, about a hundred protesters gathered in Zhanaozen, demanding an end to Chinese projects in Kazakhstan (Azattyk, 2019). On the same day, a series of rallies proclaiming “We are against Chinese expansion” took place in Nur-Sultan, Aktobe, and Shymkent.

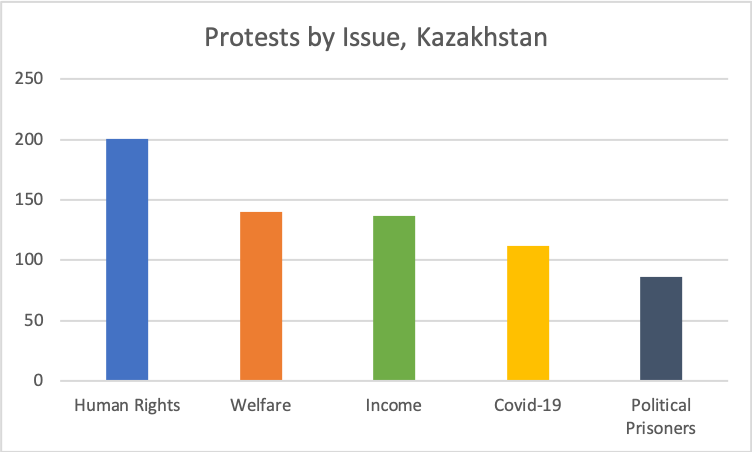

The most significant protests in Kazakhstan over the past two and a half years were focused on the transition of political power from decades-long ruler Nursultan Nazarbayev to his anointed successor Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. Over 780 protests have occurred in Kazakhstan since 2018, with all but 47 of them coming since Tokayev became president. One quarter of the protests in the country have focused on political reform and 20% related to demands for more state welfare, which was one reason Nazarbayev stepped down in 2019 (see graph below based on CAPT data).

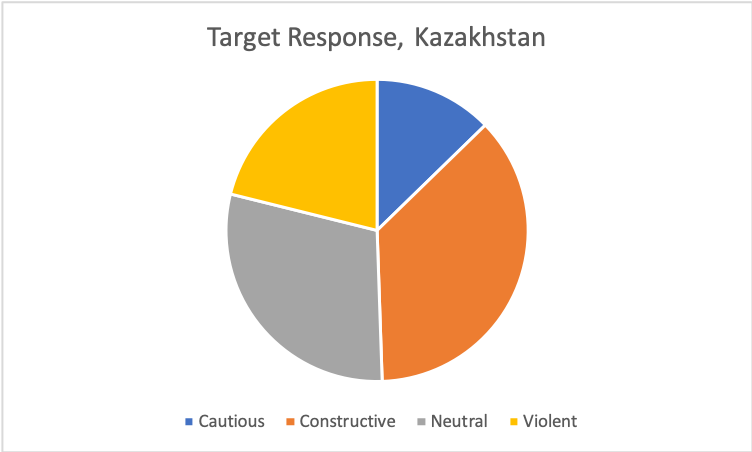

Kazakhstan also recorded the highest rate of violent responses to protests, with just over a quarter of all protests ending in arrests or the use of force (see chart below based on CAPT data), compared with just 5% in neighboring Kyrgyzstan. The government passed the Law on Peaceful Assembly in May 2020 which did not remove the requirement for protesters to obtain a permit from the government to hold rallies and pickets (Human Rights Watch 2020). According to regression analysis conducted by Oxus Society, protesters’ connection to opposition groups has the biggest effect on government response, associated with an 11-person increase in arrests compared to a protest not linked to any groups. Similarly, target-type had an impact on likelihood of force, with local and national government each associated with a 4-person increase in arrests compared to a protest held against any other actor.

Kyrgyzstan

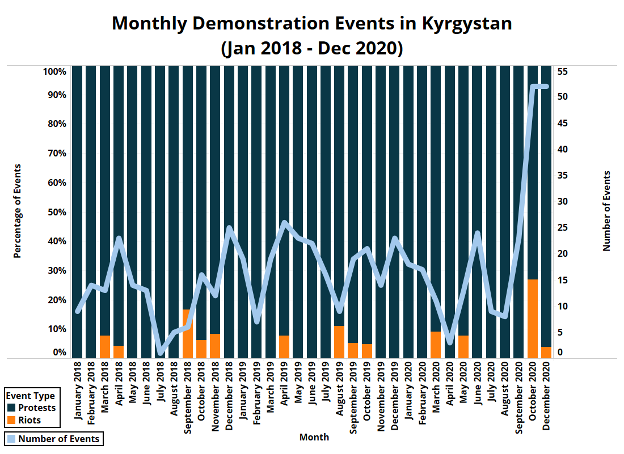

More recently, there has been a spike in demonstrations in Kyrgyzstan, spurred by dissatisfaction over election results. A spike in violent demonstrations was reported the week after the 4 October 2020 parliamentary elections, as opposition claimed that vote-buying and other irregularities marred the polls. The discontent about the election quickly turned into a series of violent demonstrations, as a result of which the country’s then-president, Sooronbay Jeenbekov, was replaced by another former politician, Sadyr Japarov. Japarov was one of the convicted politicians that was freed from prison by his supporters, joining anti-election demonstrations. Such a sudden change is not unprecedented in Kyrgyzstan, as the country previously tackled similar demonstrations and power shifts around elections (RFE/RL, 6 October 2020). However, for over a year prior to October 2020, demonstrations have primarily been driven by other ongoing issues — many of which are shared by other countries across the region — such as political repression, labor rights, and state control over civil society. The structure of ACLED data allows for the tracking of the shift in demonstration dynamics over time, especially with regard to the use of violence by demonstrators, or rioting. The graph below, for example, depicts how the spike in demonstrations in late 2020 (blue line in the graph below based on ACLED data) is driven by a rise in the proportion of demonstrations in which demonstrators engage in violence (orange bars in the graph below based on ACLED data).

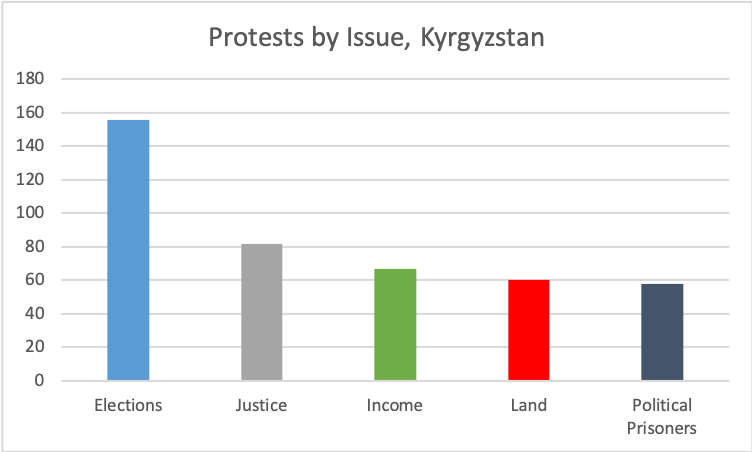

CAPT data indicate that the spike in protests in October was linked to the elections (see graph below based on CAPT data), with the dataset recording 156 election-related protests (25% of the total protests), almost all of which have come since October 2020. Other common issues that have caused protests in Kyrgyzstan include those targeting the judicial system (13% of protests) and calling for the release of political prisoners (10% of protests). A number of these prisoners, including former president Almazbek Atambayev, who was jailed in 2019, and convicted kidnapper Sadyr Japarov, were sprung from jail amid protests against the election results on 5 October. Since Japarov became acting president on 16 October, protesters have come out to oppose his constitutional amendments to return the country to a presidential system. A weekly march against the so-called “Khanstitution” took place in Bishkek from mid-October until the amendments were adopted in the 10 January 2021 election.

Beyond national politics, Kyrgyzstan, which is rich in coal, gold, and uranium, has seen a sharp uptick in protest activities involving the country’s extractive sector — which today accounts for nine percent of demonstrations recorded by the CAPT there since 2018. A large number of these are focused on environmental impact. They have had some success. After at least seven protests against uranium mining in 2019, parliament passed legislation banning this form of mining in the country (Reuters, 2019).

Like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan has seen a rise in China-related protests in recent years and a significant number of these have overlapped with mining issues. In August 2019, hundreds of locals clashed with workers from a Chinese mining company Jhong ji Mining at the Solton Sary mine in Naryn after accusing the company of poisoning the local water supply (SCMP 2019). Anti-China sentiments have risen since 2018 when a malfunction at Bishkek’s main power plant led to a five-day blackout when Chinese company TBEA tried to upgrade the station (The Diplomat 2018). January 2019 saw the largest anti-China protest in the CAPT’s record, with 500 people gathering on Ala-Too Square in Bishkek to voice their concerns about Beijing’s growing influence (RFE/RL 2019). These sentiments have proven costly for both countries, putting large-scale investment projects on hold. In February 2020, local protests led to the cancellation of a $280 million Chinese-funded logistics center (Reuters 2020). During the power vacuum following the October parliamentary elections, around 400 protesters seized the Chinese-owned Ishtamberdi gold mine, expelling the Chinese workers, although this was part of a broader situation in which at least 17 economic assets, both local and foreign-owned, were seized by protesters (Kaktus 2020).

Uzbekistan

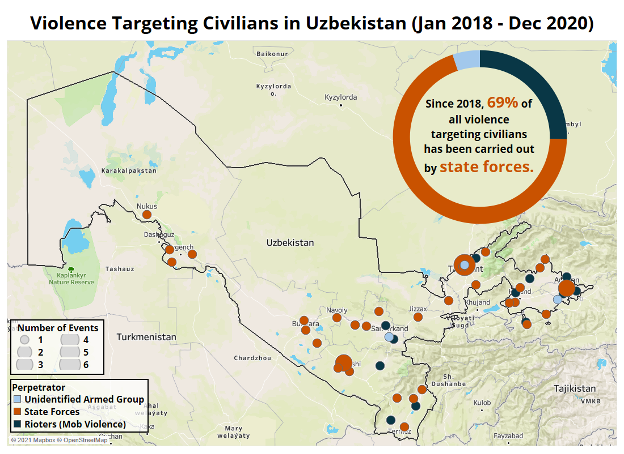

ACLED tracks the use of force by Uzbek government authorities such as the police, security services, and the National Guard, toward civilians (see map below based on ACLED data). For example, in June 2020, security forces reportedly attacked civilians in two separate incidents for not wearing face masks during the context of the health pandemic. One of the incidents was filmed by nearby witnesses and the video showed a police officer pressing his knee into the neck of a young man in Uzbekistan’s autonomous Karakalpakstan Republic, while another person in Surkhardarya region claimed that National Guard personnel severely beat him for the same reason (RFE/RL, 17 June 2020). (For more on state repression during the coronavirus pandemic around the world, see ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker.) Earlier that month, a person was allegedly tortured to death while in police custody in Andijan, prompting an investigation and the arrest of the officers involved (Gazeta.uz, 13 June 2020).[5] The following month, a number of cases of mistreatment came to light, including that of a teacher, who was taken to the police department during an investigation into a local theft and was reportedly tortured by police officers.[6] Such examples of state repression can be seen in the map and chart below based on ACLED data.

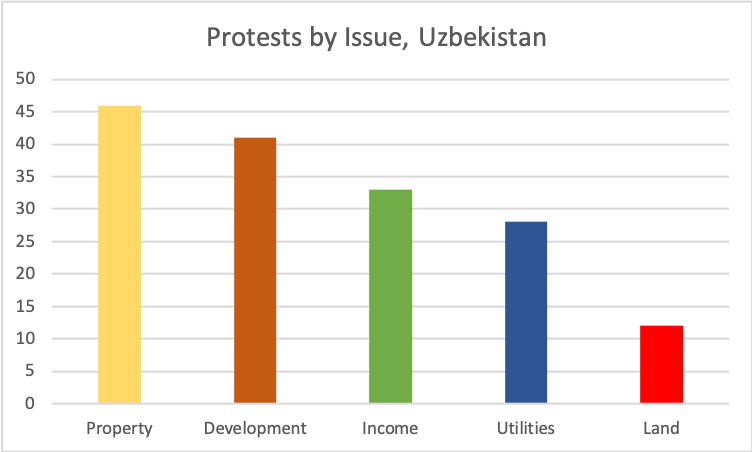

Around half of protests in Uzbekistan recorded in CAPT since 2018 have been focused on issues related to development and property disputes (see graph below based on CAPT data). Many of these have targeted building sites or efforts by the Compulsory Enforcement Bureau to demolish or evict people from their properties as the government pushes for urban redevelopment, beautification and for people to repay debts for utilities, a campaign that started in 2017 (Ozodagon, 2017). Around one quarter of protests in the country have turned violent, with residents attacking debt collectors and forcibly preventing demolition work. Self immolation has also seen a spike in recent years, with at least ten people setting themselves on fire to protest against government attempts to evict them from their homes.\

Utilities are now a prominent focus of dissent, with at least 28 protests linked to water, gas, and electricity supplies. In late 2018, around 70 locals in Karakalpakstan blocked a road and demanded that the authorities resume gas supplies to their homes, sparking a wave of similar demonstrations in other regions across the country (The Diplomat, 2019). More recently, in December 2020, after a system failure left hundreds without electricity in Muzrabat district, around 50 people blocked a road and set tires on fire, resulting in electricity being swiftly restored (Kun.uz, 2020). Labor issues are also emerging as a source of contention as the country continues to open to investors and modernize its economy. In October 2020, police and the National Guard had to put down a riot at a gas plant in Guzar over unpaid wages, with at least a thousand workers ransacking the facility (RFE/RL 2020). The management company was forced to give employees their back pay after the incident. CAPT data indicate that the targets of protests in Uzbekistan have opted for a constructive or neutral response to protests in two thirds of cases, the highest in the region.

Tajikistan

In the Ferghana Valley, where the borders of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan converge, violent confrontations between locals and state forces have been a longstanding concern. Disputes between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are particularly frequent as almost half of the 971-kilometer-long border territory remains contested, creating challenges for local populations hoping to address infrastructure and economic-related issues in the region. Disagreements over the connection of Tajikistan’s fertile Vorukh exclave to the mainland only adds to the disorder.

Contention in the borderland has been ongoing for decades, mainly over the use of land and water resources, as local livelihoods rely on agriculture and livestock. Throughout the last century, the border communities have occasionally managed to establish a delicate balance, preventing disagreements from escalating into open conflict (Reeves, 2014). Some historical studies have found that following the separation of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan from the Soviet Union in 1991, patriotic discourse and an emphasis on ethnicity exacerbated existing disputes, as control over scarce arable land became a symbol of national sovereignty (Matveeva, 2016; Murzakulova, 2017). Both states claimed rights to the border areas based on contradictory interpretations of historical evidence, halting border demarcation work and the development of infrastructure in the region, further complicating the situation and fueling tensions (The Diplomat, 2 August 2019). (For more, see the ACLED analysis piece entitled Everlasting or Ever-Changing? Violence Along the Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan Border.)

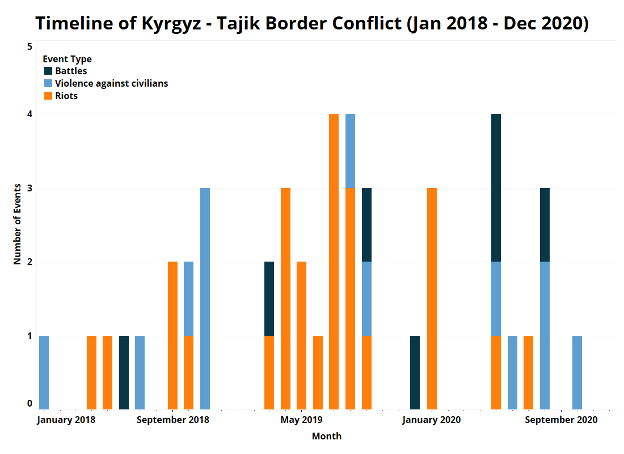

As the problem remains unresolved, ACLED continues to record intermittent clashes along the borderlines — which continue despite the global coronavirus pandemic. This violence has taken the form of armed clashes, violence against civilians, and mob violence (see graph below based on ACLED data).

But another border region of Tajikistan, Viloyati Mukhtori Kuhistoni Badakhshon (also known as GBAO), has been the focal point of protest in the country. According to the CAPT, almost half of the protests in Tajikistan since 2018 have occurred in this region, which has a long legacy of resistance to central government. Tensions with the authorities flared in late 2018 after President Emomali Rahmon publicly reprimanded GBAO officials for failing to bring the region under control. Shortly after, a policeman shot and wounded three local men, sparking a 150-person protest as locals demanded an investigation into the incident (Eurasianet, 2018). CAPT recorded 12 further demonstrations targeted at law enforcement in the GBAO, albeit nine of these were linked to the arrest of three local men from Rushon, who were accused of drug trafficking (Akhbor, 2019).

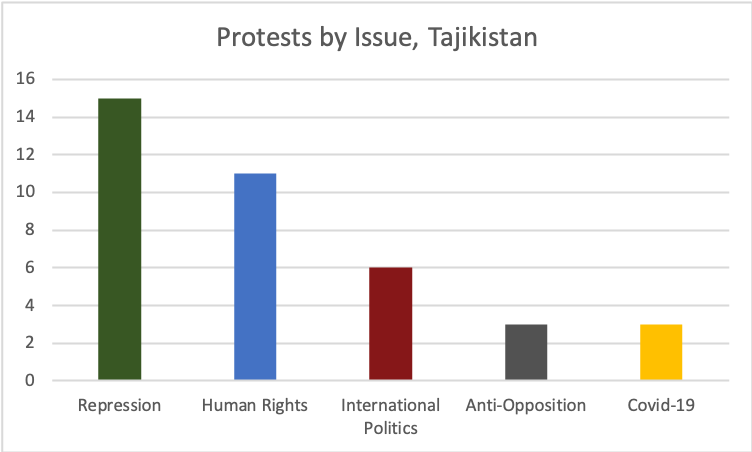

Not all protests in the country are anti-government (see graph below based on CAPT data). Tajikistan has a significant number of youth organizations who conduct campaigns in support of the regime. Protesters targeting embassies and civil-society groups generally consist of women and student activists from the youth wing of the ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP) Sozandagoni Vatan (“Homeland Builders”), or Avangard, a self-proclaimed anti-extremist group founded with the support of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (OpenDemocracy, 2016). Targets since 2018 have included the United Nations, European Union, Iran, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, all of whom the Tajik government has accused of abetting the opposition.

Turkmenistan

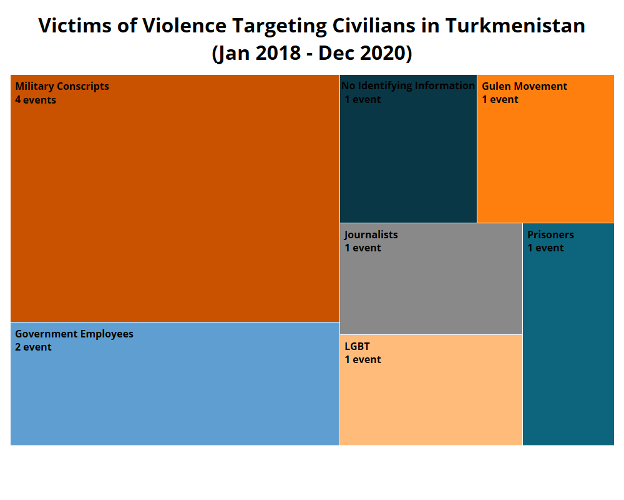

Turkmenistan is one of the most repressive countries in the world and fundamental rights remain highly restricted with tight control over media and rampant self-censorship (HRW, 2020). The majority of violence targeting civilians in the country are toward drafted soldiers (see chart below based on ACLED data), which includes forced disappearances and torture (Amnesty International, 2019). Military service is obligatory for all men for a duration of two years; poor conditions and human rights violations within the armed forces are reported by independent sources, draft evaders, or conscientious objectors.

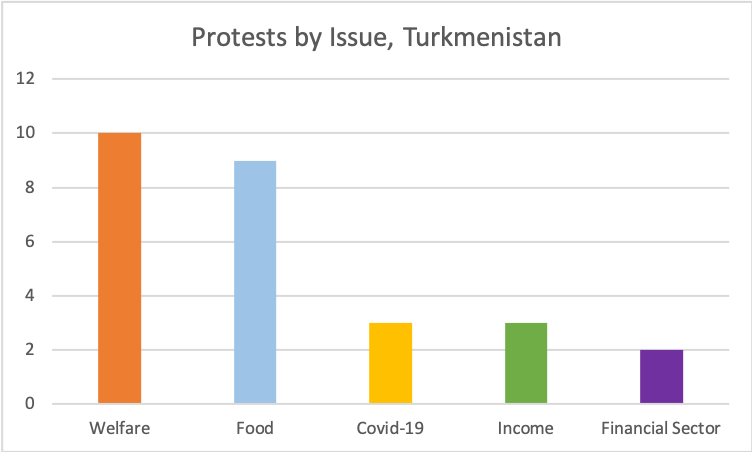

According to data from CAPT, half of the protests in Turkmenistan have been related to food shortages and rising prices for basic foodstuffs (see graph below based on CAPT data). Turkmenistan’s ongoing food crisis has been greatly exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which officials continue to publicly deny exists in the country. Shortages of state subsidized food, accelerating since 2016, have worsened in recent years, sparking a number of demonstrations in this tightly-controlled country. Turkmenistan’s main form of assistance has long been government-subsidized food in state-owned stores – an affordable alternative to private bazaars. But supplies began to falter from 2015 onwards, after the fall in prices for hydrocarbons hit the Turkmen state budget.

Since 2020, food shortages have led to a spike in confrontations between local officials, store owners, and the broader population. On 22 December, for example, a group of around 50 women went to the local government office in the city of Mary to protest food shortages (Turkmen News, 2020). They dispersed after being promised food. Just ten days earlier a similar protest took place in Garagum (Azathabar, 2020). Despite still not recording any cases of COVID-19, secretive government measures to fight the pandemic have caused protests on at least three occasions, all since September 2020. Traders at a bazaar in Baryamaly started throwing stones at police who had closed off the market, with the police having to back down and open the market (Khronika Turkmenistana, 2020). Almost all the protests have targeted the local government rather than the central government, headed by autocrat Gurbanguly Berdymuhamedow. This minimized threat to regime security and a desire by the local government to maintain stability might explain why protests have resulted in concessions from the target in 14 of the 18 protests recorded by CAPT.

Conclusion

The spotlights above help to underline the complementarity of the two datasets. ACLED data help policymakers to identify patterns in a spectrum of violence and dissent; including armed conflict and border clashes help policymakers to anticipate and understand political violence. Meanwhile, CAPT’s emphasis on the issue basis behind demonstrations helps to craft preemptive policies that address local grievances. The addition of target response typology in the CAPT’s codebook and ACLED’s focus on violence against civilians also helps human rights workers and activists to draw attention to human rights abuses in the region. In short, the combined coverage of the two distinct methodologies paints an even more comprehensive picture of regional dynamics.

[1] For more on ACLED’s sourcing strategy, see this primer.

[2] For more detail on CAPT coding, see the CAPT Codebook.

[3] For more on ACLED coding, see the ACLED Codebook.

[4] For more, see the ACLED Regional Overview from this time period.

[5] For more, see the ACLED Regional Overview from this time period.

[6] For more, see the ACLED Regional Overview from this time period.