Mapping Patterns of Dissent in Eurasia: Introducing the Central Asia Protest Tracker

By Bradley Jardine, Sher Khashimov, Edward Lemon, Aruuke Uran Kyzy

At a quarantine camp just outside of Tashkent in July, detainees rattled the gates to the facility, climbed on the rooftops of their temporary shipping container homes and shouted, demanding to be freed. After two days of protests, some of those interned were allowed to return home. With over 200,000 registered cases, Covid-19 will have a lasting impact on Central Asia. But lockdown measures have sparked backlash, with at least 103 protests linked to the pandemic and the region’s respective government responses since the virus began to spread in February 2020.

While Covid-19 leads the way for recent protests, hundreds of other protests took place on more typical issues, including freedom of speech, land rights, labour disputes, and welfare-related incidents. The Central Asia Protest Tracker (CAPT) dataset produced by a team at the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs mapped out a total of 981 incidents in the five Central Asian republics Kazakhstan (520 protests), Kyrgyzstan (351 protests), Tajikistan (27 protests), Turkmenistan (9 protests), and Uzbekistan (74 protests) from January 1, 2018 to August 31, 2020.

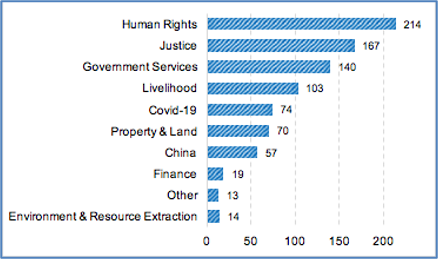

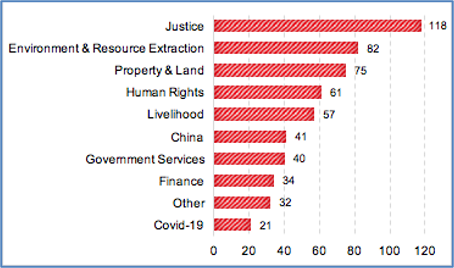

According to CAPT, over half of the protests in Kazakhstan have been related to the country’s power transition following President Nur-Sultan Nazarbayev’s resignation in March 2019. The most frequently reported issue in Kyrgyzstan, by comparison, is related to justice, and in particular, protests related to the detention of government officials such as former President Almazbek Atambayev, who was arrested on corruption charges in August 2019. Protests have steadily increased in Uzbekistan in recent years, following the death of the first President Islam Karimov in August 2016. More than half of protests have stemmed from disputes over land ownership and attempts by the government to demolish or evict people from their property. Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, meanwhile, have recorded the fewest protests, arguably reflecting the closed nature of their respective political systems and the tight control their governments exercise over political expression. In Tajikistan, half of all protests recorded have occurred in the Pamir region, which has a history of resistance to the central government. Only a handful of protests occurred in Turkmenistan since 2018, most of them related to food shortages and rising prices for staple goods.

Another key trend in both Kazakhstan and neighboring Kyrgyzstan has been the rise in protest activities relating to China or Chinese citizens. Opinion polls in the region indicate that while Russia is still viewed favorably by many Central Asians, China is viewed with greater suspicion, with 30% of Kazakhs and 35% of Kyrgyz polled reporting negative views of their eastern neighbor. Our dataset records 98 anti-China protests with all but one (in Tajikistan) taking place in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Methodology

This report draws from the data collected in CAPT, which consists of materials published online. Due to the nature of this data, which primarily consists of newspaper articles, the dataset is likely to have a substantial effect on the results of the empirical research. The reliance on reporting means that many cases of activism not considered to be “newsworthy,” that failed to attract many people, or that took place in geographically remote locations, may be missing from the final results, schewing the dataset. Furthermore, not everyone feels it is either necessary or safe to protest in public, expressing themselves in a variety of subtle ways anthropologist James Scott has called “hidden transcripts.” While we recognize that such protests, in addition to cyber protests and petitions, are vital to understanding the evolution of dissent in the region, we have limited ourselves to the following definition:

A protest action is a public expression of objection towards an idea or action of an individual or institution, including state organs, businesses, NGOs, and foreign governments, which occur in a physical space.

We coded all reported protest data we could find during our searches, including events consisting of a single individual protester. Ongoing events such as strikes, sit-ins, rallies, and hunger strikes were coded each day as a separate event. Similarly, protests occurring in multiple locations on the same day are logged in each locality as a separate incident. Despite our best efforts, wide discrepancies remain, with the Kyrgyz Ministry of the Interior listing 552 protests in 2018, while our data-gathering only confirmed a total of 107 cases that same year. Having collected the data, we coded by protest type, target type, target response, and issue being protested.[1] A more detailed overview of our methodology for data collection and coding is offered in our codebook.

Kazakhstan

Once upheld as a bastion of stability in the region, Kazakhstan has in recent years lost this reputation. Nur-Sultan Nazarbayev, who ruled the country since independence, relinquished the presidency in March 2019, partly in response to popular outrage at the death of five children in a fire. The fire galvanized the so-called “women’s protests,” a series of demonstrations across the country to draw attention to the lack of social and financial support provided to women with multiple children by the state. One fifth of the protests in the country since 2018 in our dataset are related to welfare provision, many of them having been organized by groups of women.

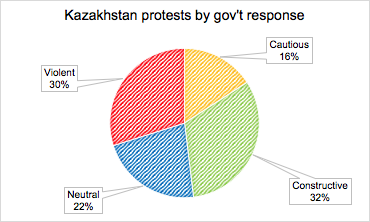

But the most significant protests in the country in the past two and half years have stemmed from the transition of power from Nazarbayev to his anointed successor, former Chairman of the Senate Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, who was elected president with 71% of the vote in a flawed election in June 2019. With Nazarbayev retaining much of his power through his chairmanship of the Security Council and leadership of the ruling Nur Otan party, protests have grown, with half of the 520 recorded protests in the country since 2018 being linked to calls for political reform or the softening of repression. Kazakhstan recorded the highest rate of violent responses to protests, with over a quarter of all protests ending in arrests or use of force. Kazakhstan has also seen new political movements emerge in response to perceived political stagnation, including the Democratic Party of Kazakhstan, founded in October 2019, and Oyan, Qazaqstan (Wake Up, Kazakhstan), a social-media savvy youth movement established in June 2019.

Our regression analysis demonstrated that the size of a protest, its target, location, and association with opposition groups matter when it comes to government response. A 10-person increase in the number of protesters is associated with a 1-person increase in arrests. Holding a protest in Nur-Sultan is associated with a 5-person increase in arrests compared to a protest held outside of the capital. Similarly, holding a protest in Almaty is associated with a 6-person increase in arrests compared to a protest held outside of Kazakhstan’s biggest city. Protesters’ connection to opposition groups has the biggest effect on government response, associated with an 11-person increase in arrests compared to a protest not linked to any groups. Finally, a protest held against a local or the national government is associated with a 4-person increase in arrests compared to a protest held against any other actor.

Protests related to government service provision and income have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Kazakhstan recorded the highest number of pandemic-related protests in the dataset, with 74 incidents. In the two weeks following the ordering of a lockdown on March 16, our dataset recorded ten protests, ranging from merchants in Pavlodar protesting against their shops being closed to calls for welfare and protests against the price of face masks in Shymkent.

Various Chinese investment projects in the country have also prompted a string of protests. On September 3, 2019, about a hundred protesters gathered in Zhanaozen demanding an end to Chinese projects in Kazakhstan. On the same day, a series of rallies “We are against Chinese expansion” took place in Nur-Sultan, Aktobe, and Shymkent. A total of 25 protests against joint-enterprises with China occurred in Kazakhstan during the period surveyed. Kazakh officials often refer to their country as the “buckle” in the Chinese “belt” – a reference to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)’s overland infrastructure projects linking Europe and Asia. The belt and its equivalent “road” – new maritime routes – form the basic design of the BRI. Close economic ties between the two countries have come under intense public scrutiny.

News of mass detention centers in Xinjiang began to make headlines in 2017 around the world, with figures since estimating the forceful detention of at least 1.5 million Muslim minorities in the region. The issue of ethnic Kazakh and Kyrgyz detainees in Xinjiang was first raised in summer 2018 by Central Asian activists who were members of the Almaty-based Atajurt Eriktileri association. The Kazakh government has sought to stifle news of concentration camps in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), and arrested Atajurt’s leader Serikzhan Bilash (later released) in March 2019, fearing the issue would disrupt the country’s trade relations with China. Nevertheless, protests relating to the situation in the XUAR have been growing, with 13 cases recorded in the dataset.

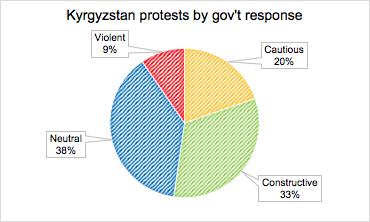

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, having had two revolutions, remains the region’s most open political system, affording greater opportunities for legal protests to take place. According to CAPT, the government of Kyrgyzstan has used violent means less frequently than neighboring governments, with just 7% of protests being suppressed by force, as opposed to 26% in Kazakhstan.

The leading causes of protests in Kyrgyzstan since 2018 have been issues of justice. This includes issues of police brutality or repression (7%), the proceedings of the court system (15%), and protests calling for the release of political prisoners (15%). Many protests calling for the release of political prisoners, most notably former President Almazbek Atambayev (sentenced in June 2020 for corruption), Sapar Isakov, former prime minister (sentenced in December 2019 for corruption), and Sadyr Japarov, a lawmaker jailed in August 2017 on hostage-taking charges. While we have opted to classify any protest where those protesting claim that they are calling for the release of “political prisoners,” there is clearly a difference between what Scott Radnitz called “elite-led protests,” where members of a politician’s patronage networks comes out in support of them, and protests calling for the release of human rights activists or opposition politicians on politically-motivated charges.

Kyrgyzstan remains rich in mineral wealth, including coal, gold, and uranium. But mining, the source of 10% of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP, also remains a subject of contention with local people. Ten percent of the protests recorded in Kyrgyzstan since 2018 by CAPT had a link to the extractive industries, often related to the impact of mining on the local environment. Protesters have met with some success. After at least seven protests against uranium mining in 2019, in May that year parliament passed legislation to ban uranium mining in the country.

Kyrgyzstan has also witnessed a sharp uptick in anti-China protests in recent years, primarily focused on the extractive sector, where half of the protests have targeted Chinese companies. Anti-China sentiments have risen since 2018 when a malfunction at Bishkek’s main power plant led to a five-day blackout while Chinese company TBEA attempted to carry out an upgrade. January 2019 saw one of the largest anti-China protests in the region to date, when 500 people gathered in Bishkek’s Ala-Too Square to voice their concerns over increased Chinese influence in the country and call on the 12,000 Chinese workers in the country to go home. In August 2019, hundreds of locals clashed with workers from a Chinese mining company Jhong ji Mining at the Solton Sary mine in Naryn after accusing the company of poisoning the local water supply. In February, following at least four local protests by locals claiming that China was trying to seize Kyrgyz land, plans to build a $280 million Chinese-funded logistics center were abandoned. The Kyrgyz government has a difficult balancing act between placating local sentiments and pleasing Beijing, the country’s leading creditor, investor, and trade partner.

Tajikistan

Protests remain a relatively rare occurrence in Tajikistan, a country that saw bloody riots in February 1990 and opposing demonstrations in the spring of 1992 that descended into civil war. Half of the protests recorded in CAPT occured in the country’s Pamir region, which has a history of resistance to the state.

After local former warlord and organized criminal leader Tolib Ayombekov killed the local head of the security services in July 2012, the central government sent in the military, killing at least 20 civilians. Yet the local strongmen the government targeted, including Ayombekov, remain at large. Tensions with the authorities flared again in late 2018 after President Emomali Rahmon publicly reprimanded local authorities for not bringing the region under control, and threatened to send in the army. Shortly after, when a police officer shot and wounded three local men, around 150 locals gathered by the regional administration to demand an investigation. CAPT recorded 11 further protests against law enforcement in the area, although nine of these were linked to the arrest of three local men from Rushon, who were accused of drug smuggling.

Many of the country’s rare protests in recent years have targeted foreign governments accused of aiding or providing asylum to members of the country’s political opposition, including the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), which was banned in 2015. Protesters targeting embassies usually consist of disgruntled women or student activists from the youth wing of the ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP) Sozandagoni Vatan (“Homeland builders”), or Avangard, a self-proclaimed anti-extremist group founded with the support of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Targets since 2018 have included the United Nations, European Union, Iran, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, all of whom the Tajik government has accused of abetting the opposition.

Turkmenistan

On May 13, 2020, an unprecedented one-thousand strong crowd reportedly gathered in the center of Turkmenabat to voice their frustration with the lack of government response to freak winds and torrential rains that left their homes devastated. If the figures for the rally are accurate, this would be the largest public protest to take place in Turkmenistan since 1995. But it has been food shortages that have been the primary cause of the handful of protests recorded in the country since 2018.

Turkmenistan’s ongoing food crisis has been greatly exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, which officials continue to publicly deny exists in the country. Shortages of state subsidized food, accelerating since 2016, have worsened in recent years, sparking a number of demonstrations in this tightly-controlled country. The country’s main form of assistance has long been government-subsidized food in state-owned stores – an affordable alternative to private bazaars. But supplies began to falter from 2015 on after the fall in prices for hydrocarbons hit the Turkmen state budget.

This year, food shortages have led to a spike in confrontations between local officials, store owners, and the broader population. On April 3, 2020, several dozen women from villages on the outskirts of Mary blocked the main highway connecting the city to the rest of the country, before marching on the provincial administration office to raise the issue of shortages. Officials were quick to respond by dispatching a truck with two-kilogram sacks of flour for each of the demonstrators to pacify them. Similarly on May 10, a group of women in Dashoguz Province were waiting in line to buy flour when they happened to see the District Chief Serdar Meredov walking by. The women accosted the government official, leaving him to flee the scene and request police assistance.

Turkmenistan’s domestic food production meets roughly 40 percent of national demand, with the rest of the country’s food supplies being imported from neighboring countries. About 80 percent of these come from Iran, which closed its border at the start of 2020, throwing Turkmenistan into a state of crisis. As shortages and Covid-19 restrictions bit into the local economy, prices for food on the free market began to skyrocket, according to a recent Human Rights Watch report.

In the past 12 months, the market price of flour rose by 50 percent, while the price of cooking oil increased by 130 percent. Other staples, such as potatoes, disappeared entirely following the closure of the Iranian border. As the job market has collapsed in the face of Covid-19 border restrictions, the lines for state shops have only grown longer, with fights breaking out. To counteract the issue, the country has imposed rations and limitations on purchasable quantities of staple foods. In some areas, flour rations have been cut from five to just three kilograms per month. Despite tensions, state media continues to paint a positive image, showing images of fully-stocked, orderly shops around the country.

Uzbekistan

Protests have been infrequent throughout Uzbekistan’s independent history. When thousands of residents of Andijon came out to protest the arrest of 23 local businessmen on charges of Islamic extremism in May 2005, the central government sent in the army, killing hundreds of people. With the death of Islam Karimov, who had ruled the country with an iron fist since 1989, a new course has been charted by his successor Shavkat Mirziyoyev, relaxing repression, opening the economy, and boosting regional relations without de-centralizing power.

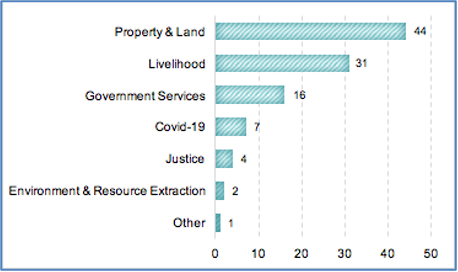

But as the country has gradually become more open, protests have increased. Over half of the 74 recorded protests in the country since 2018 have been related to land and property. Many of these have targeted building sites or efforts by the Compulsory Enforcement Bureau to demolish or evict people from their properties as the government pushes for urban redevelopment, beautification and for people to repay debts for utilities, a campaign started in 2017. A number of the incidents have been violent. On February 14, dozens of local residents of the Surkhandarya region attacked members of a working group who had arrived to check the legality of their houses. Furthermore, at least five people have set themselves on fire to protest against government attempts to evict them from their homes.

Utilities have also been a focus of dissent, with at least 10 protests linked to water and gas supplies. In late 2018, a wave of protests started in Karakalpakstan, when around 70 locals blocked a road and burned car tires in protest, demanding that local authorities resume natural gas supplies to their homes. That same day, drivers in Bakht blocked a major inter-city highway, bringing traffic to a complete standstill in protest against the unscheduled closure of a methane station that left long lines of cars without fuel. One day later, residents in Andijon gathered to protest natural gas shortages. They were followed in the coming week by protesters in Ferghana and then back in Karakalpakstan.

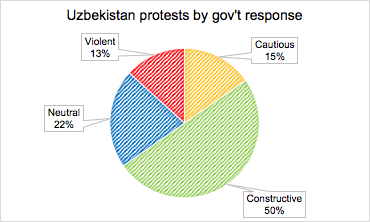

The government has been relatively responsive to popular protests, promising to resolve the situation or actually making a concession in one third of cases. Most recently, on August 11, the Tashkent municipal government scrapped plans to revise the boundaries of districts within the capital city following days of protests by residents of those neighborhoods. The head of one of these neighborhoods told residents that the plans had been abandoned due to their concerns.

Looking Forward

Over the period assessed, Kazakhstan has proven to be the most violent in quelling dissent with the regime in a state of high-alert amid its ongoing transition. Uzbekistan, meanwhile, has seen an emergence of violent activism, much of it targeted at attempts by the state to requisition their land or property. Although the sample size was small at just 9 incidents, Turkmenistan’s authorities often prove the most quick to grant concessions, fearing that minor events may trigger mass movements. In the cases of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the poorest states in the region, elite-led protests are common-place; in the case of the latter, protests are often government-supported and aim to clamp down on the opposition. And in the Kyrgyz case they often call for the release of political prisoners, most often jailed former officials.

Over the coming year, Covid-19 will likely accelerate some of the key protest dynamics in the region, with rising unemployment, falling remittances, and state welfare pushed to its limit. Turkmenistan offers an extreme case, in this regard, with the pandemic’s closing borders leading to a massive drop in food supplies, leading to an unusual spike in protest activity. Kazakhstan, meanwhile, has seen a string of anti-debt protesters as citizens are unable to pay their mortgages, leading to requests for government aid. Across the region, wage arrears and failure to deliver on promised wage increases for essential labor amid the pandemic have become another source of public outrage.

China will also continue to draw public resentment, as declining energy prices lead to government’s falling even deeper into the pockets of China’s state-owned banks, generating renewed fears of expansion. As jobs grow scarce amid the pandemic, Chinese laborers will likely become a convenient source of public anger – an issue that opposition movements will likely exploit to their advantage.

Finally, transition will also be a significant factor in rising dissent in future, as the transition of power in Kazakhstan and the political reforms in Uzbekistan lead to new winners and losers as new policies are implemented.

[1] To simplify the presentation of the data here, we have collapsed the 28 different issues into 11 larger categories: Livelihood (Income, Labor), Human Rights, (Elections, Gender Issues, Freedom of Assembly, Freedom of Expression, Human Rights), Justice (Political Prisoners, Repression, Justice), China, Government Services (Welfare, Relief), Utilities, Property (Property, Land, Development), Environment (Environment, Extractive Industries), Covid-19, Finance (Corruption, Financial Sector), and Other (International Politics, Animal Rights, Cultural, Identity, Food, Anti-Opposition). We have also combined response types to create four new categories: Neutral (Unknown, Nothing), Constructive (Promise, Meeting), Cautious (Dispersal, Monitoring), and Violent (Penalty, Force, Intimidation, arrests).