Kazakhstan’s Majilis Election: One-Party Dominance with a Pluralistic Face

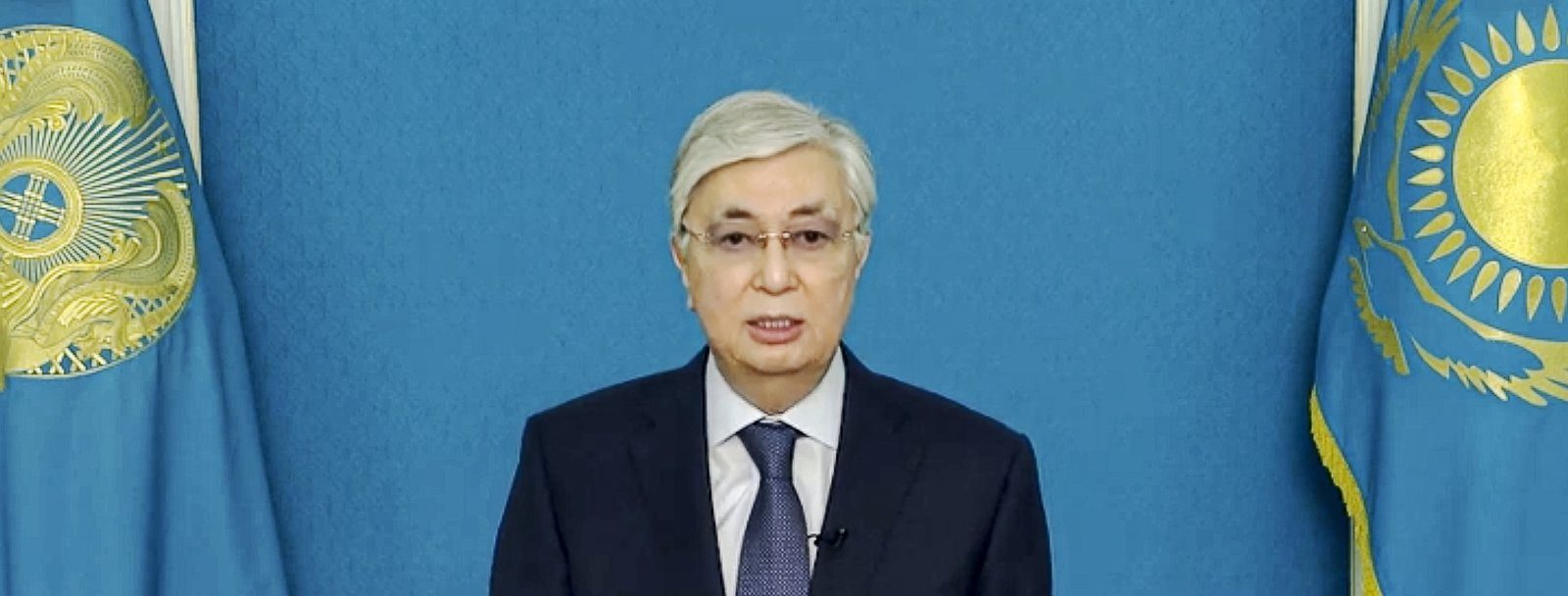

On March 19, Kazakhstan held parliamentary elections that were meant to signify the final step in President Tokayev’s “cardinal transformation” of the country’s political system. The confirmed dominance of the ruling Amanat party, coupled with President Tokayev’s landslide victory in the snap presidential elections of November 2022, indicates that political liberalization, at least at the national level, is unlikely to be achieved in the immediate future.

For decades, Kazakhstan experienced political inertia, with elections serving more as a ritual than as a meaningful political process. In response to the January 2022 unrest (known as Bloody January), President Tokayev announced ambitious electoral reforms. Previously, the lower house of parliament, Majilis, was fully elected through proportional representation, which reinforced the dominance of the ruling party Nur Otan (now Amanat). Recognizing the growing popular apathy towards electoral processes, Tokayev stressed the need for political pluralism, giving smaller parties and non-partisan candidates more freedom to compete.

The reform package included measures to reduce barriers to entry for new parties. The number of signatures required for party registration dropped from 20,000 to 5,000. A group initiative that previously required 1,000 active members from various regions now needs just 700, with full in-person participation at the founding congress. Nevertheless, the requirement still presents substantial logistical challenges for new parties, as they often do not have the organizational and material capacity to recruit enough people willing and able to travel to the founding congress. Additionally, the electoral system shifted to mixed-member majoritarian representation. Some 70 percent of 98 seats are elected through party lists with a 5% passing threshold. The remaining 30 percent of seats are then allocated by direct plurality elections in single-member districts, which allows independent non-partisan candidates to compete.

While these changes were not revolutionary, they increased the possibility of new voices entering the political arena. Civil society activism and engagement remained strong, and a renewed hope for authentic change began to form in the lead-up to March 19.

However, the electoral amendments did not provide the political pluralism many hoped to see. Activists and opposition parties found it difficult to register. Alga Kazakhstan and Namys have been repeatedly denied registration due to “incomplete applications,” although the applicants say these rejections are politically motivated.

Only two new parties were able to register: the green party Baitak and Respublika. Both have been perceived as being state organized. Azamatkhan Amirtay, the chairman of Baitak, held executive positions within state-owned companies, including the national railroad company, Kazakhstan Temir Zholy, and several pro-regime institutions, such as the National Council of Public Trust. He has not been known for promoting environmental agendas before. Beibit Alibekov, the leader of Respublika, meanwhile, publicly stated that the goal of his party was to support Tokayev’s reforms and prevent “rabid populists from coming to power.”

Five pre-existing parties that made it to the ballot were widely viewed as pro-regime and did not position themselves as the opposition but as alternative and complementary options. Auyl (“Village”) platformed itself as representative of rural interests and Ak Zhol of business interests. Neither the welfare-oriented National Social Democratic Party (OSDP) nor the formerly communist National Party of Kazakhstan have distinguished themselves from the ruling Amanat’s agenda.

Unlike party lists, single-member districts offered the possibility of greater competition and diverse outcomes. However, many prominent activists who intended to run as self-nominated independents were denied registration. Some candidates were rejected over technical discrepancies in their application forms, bank declarations, and residence registrations. Others, including prominent activist Aigerim Tleuzhan, were charged or declared suspects in criminal activities during the January unrest. Eighty-two rejected candidates sued the Central Election Commission (CEC), and 6 of them won in court, resulting in their subsequent registration. This suggests a potential disagreement and independence between the courts and the CEC.

On election day, numerous instances of fraud and violations were reported by civil society groups. MISK and Erkindik Kanatty sent trained election observers and reported pressure from CEC voting district representatives. Some observers were removed from the station for taking pictures and recording election violations. Others were prevented from observing the vote count and viewing the final result sheets. Despite these constraints, observers did manage to share video evidence of mass ballot stacking, result sheets with false final vote counts (pre-arranged before the election started), and individuals voting multiple times.

Despite promises of real competition, the election results announced on March 20 show how electoral concessions were largely performative. Amanat won 53.9% of the vote in the party lists, with Auyl, Respublika, Ak Zhol, OSDP, and National Party winning 10.9%, 8.6%, 8.4%, 6.8%, and 5.2% respectively. Out of 29 single-member districts, 23 were won by Amanat-nominated candidates.

Independent candidates’ requests for recounts within single-member districts were denied without explanation. A survey of result sheets showed some independent candidates winning at voting stations where observers were present, while stations without observers reported extremely wide margins in favor of Amanat. This suggests the presence of independent observers significantly impacted transparency and compliance with the rules and led to a “cleaner,” albeit imperfect, election in those districts.

Six self-nominated candidates won Majilis seats in single-member districts. Two of them are current members of Amanat: blogger and journalist Daulet Mukayev and MMA athlete Ardak Nazarov. Both were members of a pro-government party, Adal, which merged into Amanat in 2021. Two other candidates had prior political experience. Businessman Yerlan Stambekov was formerly with Amanat’s predecessor, Nur Otan, for 19 years. He left the party after the presidential election of 2019, citing his disagreement with the party’s direction and the regime’s repression of peaceful protesters. Journalist Yermurat Bapi was a member of OSDP but was expelled due to internal disagreements. Bapi maintains connections with Kazakhstani dissidents-in-exile while also being a member of the National Kurultai (Congress), a presidential consultative body. Daniyar Kaskarauov, who is president of a fight club, does not seem to have prior political experience or a platform.

Abzal Kuspan, a lawyer from Western Kazakhstan, has a more consistent record of political activism in his high-profile court cases. He defended the victims of Zhanaozen in 2012, as well as a leader of a Sufi association in Almaty, who was deemed a political prisoner by human rights organizations. During Bloody January, Kuspan spoke out with demands for political reforms and was arrested for 10 days for “participating in an illegal rally.” While allegations of electoral fraud and close connection to Amanat cloud his victory, Kuspan may be the most independent person in the new Majilis. Together, the non-Amanat deputies could use their platform to voice dissenting opinions, put pressing issues on the agenda, and increase political pluralism.

Ultimately, Amanat successfully secured its dominance in the new Majilis with over 63 out of 98 seats. The remainder were claimed by friendly pro-regime parties and four independent candidates. Admittedly, it may not be the pluralism voters were promised, but it is not a full reenactment of Nazarbayev-era theatrics, where Nur Otan could win all seats (as it did in 2007), or where turnout was inflated to 95% (as in the presidential election of 2015).

The turnout in this election was only 54 percent. At the very least, this suggests results were less falsified than usual. Although OSCE observers suspected the number of ballots received might exceed the number of those who voted, there was no evidence of grand-scale turnout inflation to the level of previous elections. This year, the government barred universities from forcing students to vote en masse in an organized manner, which could have contributed to the low turnout. Because a comparatively small fraction of society turned out to vote, there is a certain cost to ruling-party legitimacy. With some independents allowed to run and a few to secure seats, the reforms still demonstrate small and necessary steps in the incremental institutional evolution.

One significant development is the rise of civic engagement. People are active, invested, and hungry for progress. Things might not have changed in the overall government composition, and reforms might not have accomplished the promised improvements, but the general mood and attitude of civil society organizations and the population have improved. They demand accountability and representation, and if not through this election, then perhaps in the future.

Akbota Karibayeva is a Ph.D. student at the George Washington University who specializes in political regimes and geopolitics in Central Asia.

Cole Anselmo is MPhil Russian and Eastern European Studies candidate at the University of Oxford, focused on Central Asia, human rights law, defense, and security.